This is a revised version of two ethnobotany posts that appeared previously on Awkward Botany: White Man’s Foot, part one and part two. Plantains have a long history of ethnobotonical uses, as well as a bad reputation of being pesky, hard-to-eliminate weeds. The two most common introduced plantain species in North America are broadleaf plantain (Plantago major) and lanceleaf plantain (Plantago lanceolata). Wherever our daily travels take us, chances are there is a plantain growing nearby.

———————

Plantago major is in the plantain family (Plantaginaceae) a family that consists of at least 90 genera, including common ornamental plants like Veronica (speedwells), Digitalis (foxgloves), and Antirrhinum (snapdragons). The genus Plantago, commonly known as plantains, consists of around 200 species distributed throughout the world in diverse habitats. Most of them are herbaceous perennials with similar growth habits.

Originating in Eurasia, P. major now has a cosmopolitan distribution. It has joined humans as they have traveled and migrated from continent to continent and is now considered naturalized throughout most temperate and some tropical regions. P. major has a plethora of common names – common plantain being the one that the USDA prefers. Other names include broadleaf plantain, greater plantain, thickleaf plantain, ribgrass, ribwort, ripplegrass, and waybread. Depending on the source, there are various versions of the name white man’s foot. Along the same line, a common name for P. major in South Africa is cart-track plant.

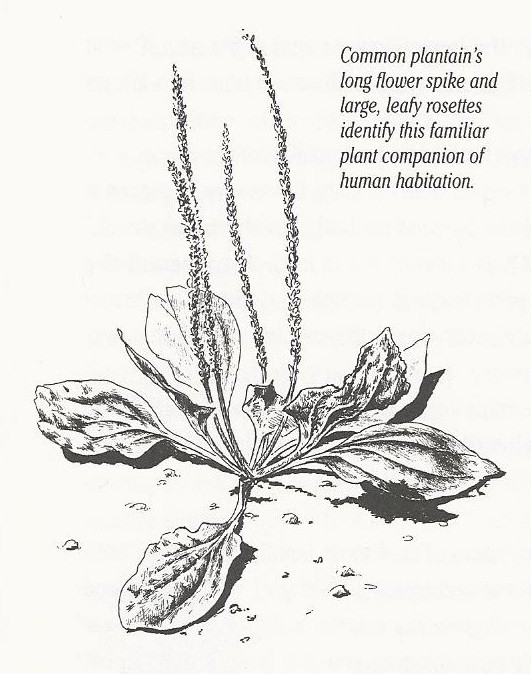

common plantain (Plantago major)

Common plantain starts by forming a rosette of broad leaves usually oriented flat against the ground. The leaves are egg-shaped with parallel veins; occasionally, leaf margins are faintly toothed. The inflorescence is a leafless spike up to 20 centimeters tall or taller with several tiny flowers that are a dull yellow-green-brown color. The flowers are wind pollinated and highly prone to self-pollination. The fruits are capsules that can contain as many as 30 seeds; an entire plant can produce as many as 15,000 seeds. The seeds are small, brown, sticky, and easily transported by wind or by adhering to shoes, clothing, animals, and machinery. They require light to germinate and can remain viable for up to 60 years.

Common plantain prefers sunny sites but can also thrive in part shade. It adapts to a variety of soil types but performs best in moist, clay-loam soils. It is often found in compacted soils and is very tolerant of trampling. This trait, along with its low-growing leaves that easily evade mower blades, explains why it is so common in turf grass. It is highly adaptable to a variety of habitats and is particularly common on recently disturbed sites (both natural and human caused). It is an abundant urban and agricultural weed.

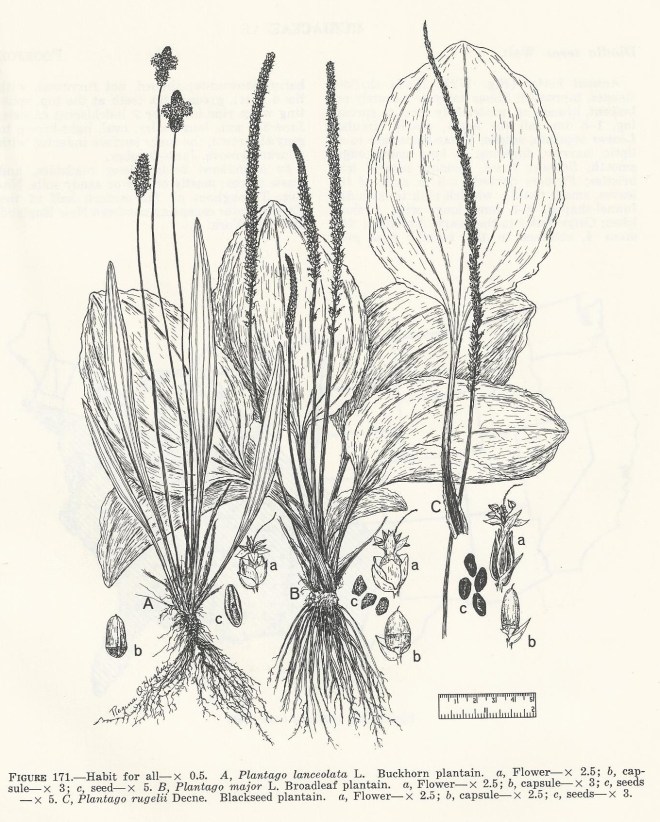

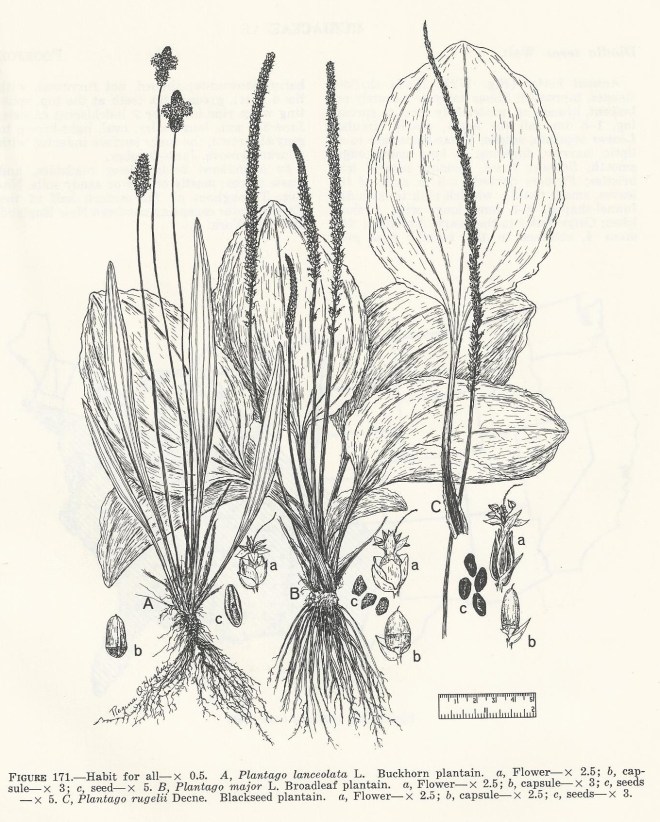

Illustration of three Plantago species from Selected Weeds of the United States (Agriculture Handbook No. 366) circa 1970

Even though it is wind pollinated, its flowers are visited by syrphid flies and various bee species which feed on its pollen. Several other insects feed on its foliage, along with a number of mammalian herbivores. Cardinals and other bird species feed on its seeds.

Humans also eat plantain leaves, which contain vitamins A, C, and K. Young, tender leaves can be eaten raw, while older leaves need to be cooked as they become tough and stringy with age. The medicinal properties of P. major have been known and appreciated at least as far back as the Anglo-Saxons, who likely used a poultice made from the leaves externally to treat wounds, burns, sores, bites, stings, and other irritations. It has also been used to stop cuts from bleeding and to treat rattlesnake bites. Apart from external uses, the plant was used internally as a pain killer and to treat ulcers, diarrhea, and other gastrointestinal issues.

P. major has been shown to have antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and other biological properties; several chemical compounds have been isolated from the plant and deemed responsible for these properties. It is for this reason that P. major and other Plantago species have been used to treat such a diverse number of ailments. The claims are extensive and worth exploring. You can start by visiting the following sites:

Concerning their cosmopolitan nature: “Although both plantains [P. major and P. lanceolata] are Eurasian natives, they have long been thoroughly naturalized global residents; the designation ‘alien’ applies to them in the same sense that all white and black Americans are alien residents.”

In which I learned a new term: “Both species are anthropophilic (associate with humans); they frequent roadsides, parking areas, driveways, and vacant lots, occurring almost everywhere in disturbed ground. Where one species grows, the other can often be found nearby.”

Medicinal and culinary uses according to Eastman: “Plantains have versatile curative as well as culinary properties; nobody need go hungry or untreated for sores where plantains grow. These plants contain an abundance of beta carotene, calcium, potassium, and ascorbic acid. Cure-all claims for common plantain’s beneficial medical uses include a leaf tea for coughs, diarrhea, dysentery, lung and stomach disorders, and the root tea as a mouthwash for toothache. … Their most frequent and demonstrably effective use as a modern herb remedy, however, is as a leaf poultice for insect bites and stings plus other skin irritations. The leaf’s antimicrobial properties reduce inflammation, and its astringent chemistry relieves itching, swelling, and soreness.”

Even the seeds are “therapeutic”: “The gelatinous mucilage surrounding seeds can be readily separated, has been used as a substitute for linseed oil. Its widest usage is in laxative products for providing bulk and soluble fiber called psyllium, mainly derived from the plantain species P. ovata and leafy-stemmed plantain (P. psyllium), both Mediterranean natives.”

“Plantain, ‘the mother of worts,’ is present in almost all the early prescriptions of magical herbs, back as far as the earliest Celtic fire ceremonies. It isn’t clear why such a drab plant – a plain rosette of grey-green leaves topped by a flower spike like a rat’s-tail – should have had pre-eminent status. But its weediness, in the sense of its willingness to tolerate human company, may have had a lot to do with it. The Anglo-Saxon names ‘Waybroad’ or ‘Waybread’ simply mean ‘a broad-leaved herb which grows by the wayside.’ This is plantain’s defining habit and habitat. It thrives on roadways, field-paths, church steps. In the most literal sense it dogs human footsteps. Its tough, elastic leaves, growing flush with the ground, are resilient to treading. You can walk on them, scuff them, even drive over them, and they go on living. They seem to actively prosper from stamping, as more delicate plants around them are crushed. The principles of sympathetic magic, therefore, indicated that plantain would be effective for crushing and tearing injuries. (And so it is, to a certain extent. The leaves contain a high proportion of tannins, which help to close wounds and halt bleeding.)”