Over the course of human history, plant species once esteemed or considered useful have been recategorized into something less desirable. For one reason or another, plants fall out of favor or wear out their welcome, and, in come cases, are found to be downright obnoxious, ultimately losing their place in our yards and gardens. The particularly troublesome ones are branded as weeds, and put on our “do not plant” lists. These plants are not only unfavored, they’re despised. But being distinguished as a weed doesn’t necessary negate a plant’s usefulness. It’s likely that the plant still has some redeeming characteristics. We’ve just chosen instead to pay more attention its less redeeming ones.

Chicory is a good example of a plant like this. At one point in time, Cichorium intybus had a more prominent place in our gardens, right alongside dandelions in fact. European colonizers first introduced chicory to North America in the late 1700’s. Its leaves were harvested for use as a salad green and its roots were used to make a coffee additive or substitute. Before that, cultivation of chicory for these and other purposes had been going on across Europe for thousands of years, and it still goes on today to a certain extent. Along with other chicory varieties, a red-leafed form known as radicchio and a close cousin known as endive (Chicorium endivia) are grown as specialty crops, occassionally finding their way into our fanciest of salads.

Radicchio di Chioggia (Cichorium intybus var. foliosum) is a cultivated variety of chicory. (via wikimedia commons)

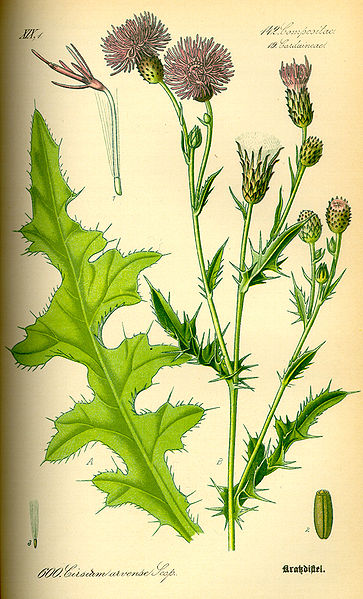

Chicory’s tough, adaptable nature and proclivity to escape cultivation have helped it become widespread, making itself at home in natural areas as well as urban and rural settings. Its perennial life history helps make it a fixture in the landscape. It sends down a long, sturdy taproot and settles in for the long haul. It tolerates dry, compacted soils with poor fertility and doesn’t shy away from roadside soils frequently scoured with salts. It’s as though it was designed to be a city weed.

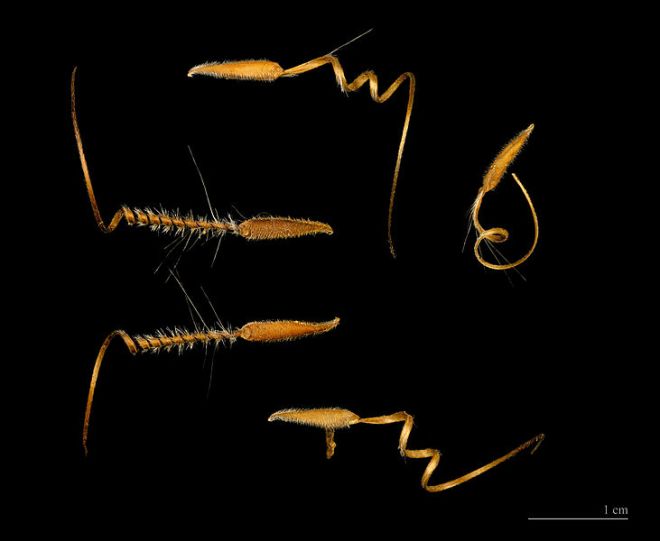

Unlike many other perennial weeds, chicory doesn’t spread vegetatively. It starts its life as a seed, blown in from a nearby plant. After sprouting, it forms a dandelion-esque rosette of leaves during its first year. Wiry, branched stems rise up from the rosette in following years, reaching heights of anywhere from about a foot to 5 or 6 feet. When broken, leaves, stems, and roots ooze a milky sap. Abundant flowers form along the gangly stems. Like other plants in the aster family, each flower head is composed of multiple flowers. Chicory flower heads are all ray flowers, lacking the disc flowers found in the center of other plants in this family. The petals are a brilliant blue – sometimes pink or white. Individual flowers last less than a day and are largely pollinated by bees. The fruits lack the large pappus found on dandelions and other close relatives, but the seeds are still dispersed readily with the help of wind, animals, and human activity.

chicory (Cichorium intybus) via wikimedia commons

The most commonly consumed portions of chicory are its leaves and roots. Its flowers and flower buds are also edible. Young leaves and blanched leaves are favored because they are the least bitter. Excluding the leaves from light by burying or covering them up keeps them pale and reduces their bitter flavor. This is standard practice in the commercial production of certain chicory varieties. The taproots of chicory are dried, roasted, and ground for use as a coffee substitute. They are also harvested commercially for use as a natural sweetener due to their high concentration of inulin.

I harvested a single puny chicory root in order to make tea. On my bike ride to work there is a small, sad patch of chicory growing in the shade of large trees along the bike path. I was only able to pull one plant up by the roots. The others snapped off at the base. So, I took my tiny root, dried and roasted it in the oven, and ground it up in a coffee grinder. I followed instructions for roasting found on this website, but there are many other sources out there. I had just enough to make one small cup of tea, which reminded me of dandelion root teas I have had. Sierra found it to be very bitter, and I agreed but still enjoyed it. I figure that wild plants, especially those growing in stressful conditions like mine was, are likely to be more bitter and strong tasting compared to coddled, cultivated ones found in a garden.

When I find a larger patch of feral chicory, I hope to try one of several recipes included in Luigi Ballerini’s book, A Feast of Weeds, as well as other recipes out there. I’ll be sure to let you know how it goes.

Are you curious to know how chicory became such a successful weed in North America? Check out this report in Ecology and Evolution to learn about the genetic explanation behind chicory’s success.