A series of posts about poisonous plants should not get too far along without discussing what may be the most poisonous plant in the world – one involved in high and low profile murders and attempted murders, used in suicides and attempted suicides, a cause of numerous accidental deaths and near deaths, developed for use in biological warfare by a number of countries (including the United States), and used in bioterrorism attacks (both historically and presently). Certainly, a plant with a reputation like that is under tight control, right? Not so. Rather, it is widely cultivated and distributed far beyond its native range – grown intentionally and used in the production of a plethora of products. In fact, products derived from this plant may be sitting on a shelf in your house right now.

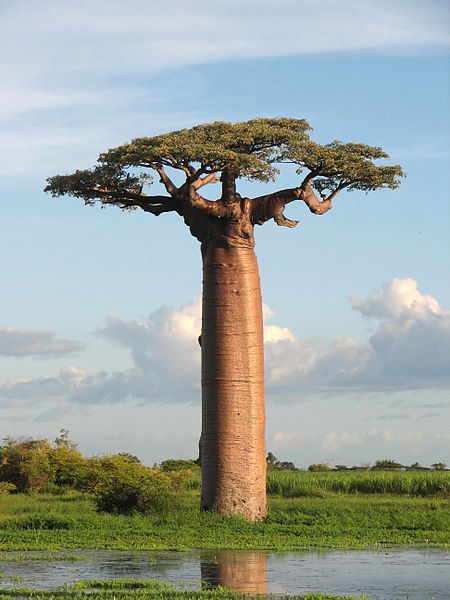

Ricinus communis, known commonly as castor bean or castor oil plant, is a perennial shrub or small tree in the spurge family (Euphorbiaceae) and the only species in its genus. It is native to eastern Africa and parts of western Asia but has since been spread throughout the world. It has naturalized in tropical and subtropical areas such as Hawaii, southern California, Texas, Florida, and the Atlantic Coast. It is not cold hardy, but is commonly grown as an ornamental annual in cold climates. It is also grown agriculturally in many countries, with India, China, and Mozambique among the top producers.

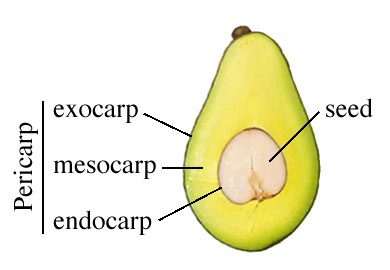

Castor bean has large palmately lobed leaves with margins that are sharply toothed. Leaves are deep green (sometimes tinged with reds or purples) with a red or purple petiole and can reach up to 80 centimeters (more than 30 inches) across. Castor bean can reach a height of 4 meters (more than 12 feet) in a year; in areas where it is a perennial, it can get much taller. Flowers appear in clusters on a large, terminal spike, with male flowers at the bottom and female flowers at the top. All flowers are without petals. Male flowers are yellow-green with cream-colored or yellow stamens. Female flowers have dark red styles and stigmas. The flowers are primarily wind pollinated and occasionally insect pollinated. The fruits are round, spiky capsules that start out green often with a red-purple tinge and mature to a brown color, at which point they dehisce and eject three seeds each. The seeds are large, glossy, bean-like, and black, brown, white, or often a mottled mixture. They have the appearance of an engorged tick. There is a small bump called a caruncle at one end of the seed that attracts ants, recruiting them to aid in seed dispersal.

All parts of the plant are toxic, but the highest concentration of toxic compounds is found in the seeds. The main toxin is ricin, a carbohydrate-binding protein that inhibits protein synthesis. The seeds need to be chewed or crushed in order to release the toxin, so swallowing a seed whole is not likely to result in poisoning. However, if seeds are chewed and consumed, 1-3 of them can kill a child and 2-6 of them can kill an adult. It takes several hours (perhaps several days) before symptoms begin to occur. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, severe stomach pain, diarrhea, headaches, dizziness, thirst, impaired vision, lethargy, and convulsions, among other things. Symptoms can go on for several days, with death due to kidney failure (or multisystem organ failure) occurring as few as 3 and as many as 12 days later. Death isn’t imminent though, and many people recover after a few days. Taking activated charcoal can help if the ingestion is recent. In any case, consult a doctor or the Poison Control Center for information about treatments.

The seeds of castor bean are occasionally used to make jewelry. This is not recommended. In The North American Guide to Common Poisonous Plants and Mushrooms, the authors warn that “drilling holes in the seeds makes them much more deadly because it exposes the toxin.” Wearing such jewelry can result in skin irritation and worse. The authors go on to say that “more than one parent has allowed their baby to suck on a necklace of castor beans.” I doubt such parents were pleased with the outcome.

Castor beans are grown agriculturally for the oil that can be extracted from their seeds. Due to the way its processed, castor oil does not contain ricin. The leftover meal can be fed to animals after it has been detoxified. Castor oil has been used for thousands of years, dating as far back as 5000 BC when Egyptians were using it as a fuel for lamps and a body ointment, among other things. Over the centuries it has had many uses – medicinal, industrial, and otherwise. It makes an excellent lubricant, is used in cosmetics and in the production of biofuel, and has even been used to make ink for typewriters. One of its more popular and conventional uses is as a laxative, and in her book, Wicked Plants, Amy Stewart describes how this trait has been used as a form of torture: “In the 1920’s, Mussolini’s thugs used to round up dissidents and pour castor oil down their throats, inflicting a nasty case of diarrhea on them.”

A couple of years ago, I grew a small stand of castor beans outside my front door. I was impressed by their rapid growth and gigantic leaves. I also enjoyed watching the fruits form. By the end of the summer, they were easily taller than me (> 6 feet). I collected all of the seeds and still have them today. I knew they were poisonous at the time, but after doing the research for this post, I’m a little wary. With a great collection of castor bean seeds comes great responsibility.

There is quite a bit of information out there about castor beans and ricin. If you are interested in exploring this topic further, I recommend this free PubMed article, this Wikipedia page about incidents involving ricin, this article in Nature, and this entry in the Global Invasive Species Database. Also check out Chapter 11 (“Death by Umbrella”) in Thor Hanson’s book, The Triumph of Seeds.