One of the concerns about introduced species becoming invasive is that they threaten to reduce the biodiversity of the ecosystems they have invaded. They do this by spreading rampantly, using up resources and space, altering ecosystem functions, and ultimately pushing other species out. In the case of certain invasive animals, species may be eliminated via predation; but plants don’t eat each other (generally), so if one plant species is to snuff out another plant species it must use other means. Presently, we have no evidence that a native plant species has been rendered extinct solely as a result of an invasive plant species. That does not mean, however, that invasive plants are not doing harm.

In a paper published in AoB Plants in August 2016, Paul O. Downey and David M. Richardson argue that, when it comes to plants, focusing our attention on extinctions masks the real impact that invasive species can have. In general, plants go extinct more slowly than animals, and it is difficult to determine that a plant species has truly gone extinct. Some plants are very long-lived, so the march towards extinction can extend across centuries. But the real challenge – after determining that there are no above-ground signs of life – is determining that no viable seeds remain in the soil (i.e. seed bank). Depending on the species, seeds can remain viable for dozens (even hundreds) of years, so when conditions are right, a species thought to be extinct can emerge once again. (Consider the story of the Kankakee mallow.)

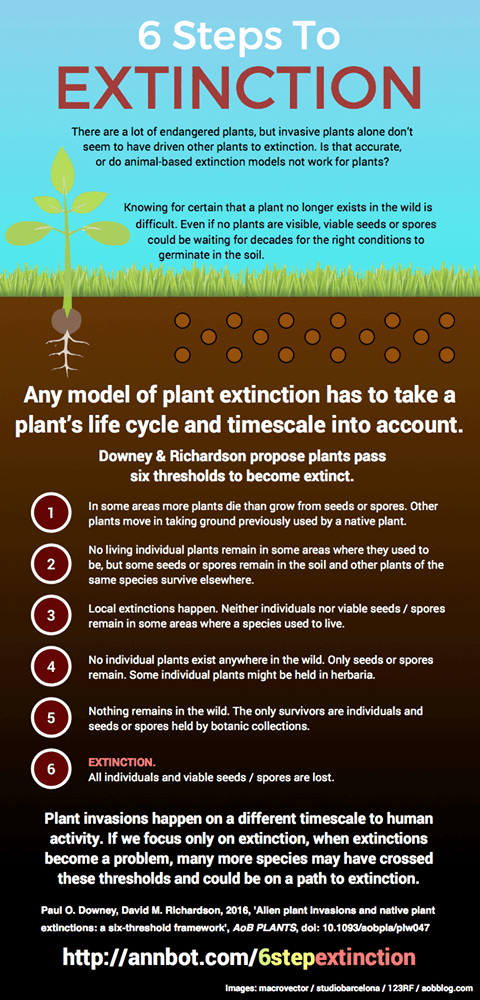

On the other hand, there is plenty of evidence that invasive plant species have had significant impacts on certain native plant populations and have placed such species on, what Downey and Richardson call, an extinction trajectory. It is this trajectory that deserves our attention if our goal is to save native plant species from extinction. As described in the paper, the extinction trajectory has six steps – or thresholds – which are defined in the infographic below:

Downey and Richardson spend a portion of the paper summarizing research that demonstrates how invasive plants have driven native plants into thresholds 1-3, thereby placing them on an extinction trajectory. In New Zealand, Lantana camara (introduced from the American tropics) creates dense thickets, outcompeting native plants. Researchers found that species richness of native plants declined once L. camara achieved 75% cover in the test sites. In the U.S., researchers found reduced seed set in three native perennial herbs as a result of sharing space with Lonicera mackii (introduced from Asia), suggesting that the alien species is likely to have a negative impact on the long-term survivability of these native plants. Citing such research, Downy and Richardson conclude that “it is the direction of change that is fundamentally important – the extinction trajectory and the thresholds that have been breached – not whether a native plant species has actually been documented as going extinct due to an alien plant species based on a snapshot view.”

Introduced to New Zealand from the American tropics, largeleaf lantana (Lantana camara) forms dense thickets that can outcompete native plant species. (photo credit: wikimedia commons)

In support of their argument, they also address problems with the way some research is done (“in many instances appropriate data are not collected over sufficiently long periods,” etc.), and they highlight the dearth of data and research (“impacts associated with most invasive alien plants have not been studied or are poorly understood or documented”). With those things in mind, they make recommendations for improving research and they encourage long-term studies and collaboration in order to address the current “lack of meta analyses or global datasets.” A similar recommendation was made in American Journal of Botany in June 2015.

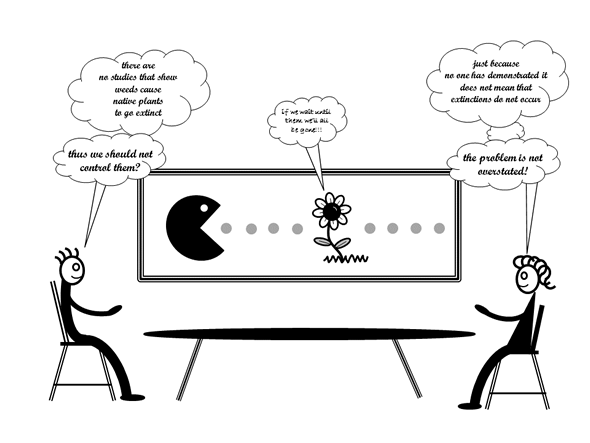

The language in this report makes it clear that the authors are responding to a certain group of people that have questioned whether or not the threat of invasive plants has been overstated and if the measures we are taking to control invasive plants are justified. The following cartoon that appeared along with a summary of the article way oversimplifies the debate:

Boy: There are no studies that show weeds cause native plants to go extinct, thus we should not control them. Plant: If we wait until then, we’ll all be gone!!! Girl: Just because no one has demonstrated it does not mean that extinctions do not occur. The problem is not overstated!

It seems to me that a big part of why we have not linked an invasive plant species to a native plant species extinction (apart from the difficulty of determining with certainty that a plant has gone extinct) is that extinctions are often the result of a number of factors. The authors do eventually say that: “it is rare that one threatening process in isolation leads to the extinction of a species.” So, as much as it is important to fully understand the impacts that invasive plant species are having, it is also important to look at the larger picture. What else is going on that may be contributing to population declines?

Observing invaded plant populations over a long period seems like our best bet in determining the real effects that invasive species are having. In some cases, as Downey and Richardson admit, “decreased effects over time” have been documented, and so “the effects [of invasive species] are dynamic, not static.” And speaking of things that are dynamic, extinction is a dynamic process and one that we generally consider to be wholly negative. But why? What if that isn’t always the case? Extinctions have been a part of life on earth as long as life has been around. Is there anything “good” that can come out of them?