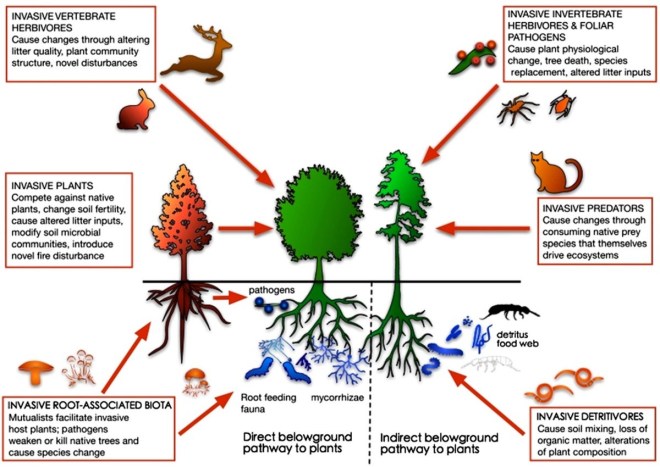

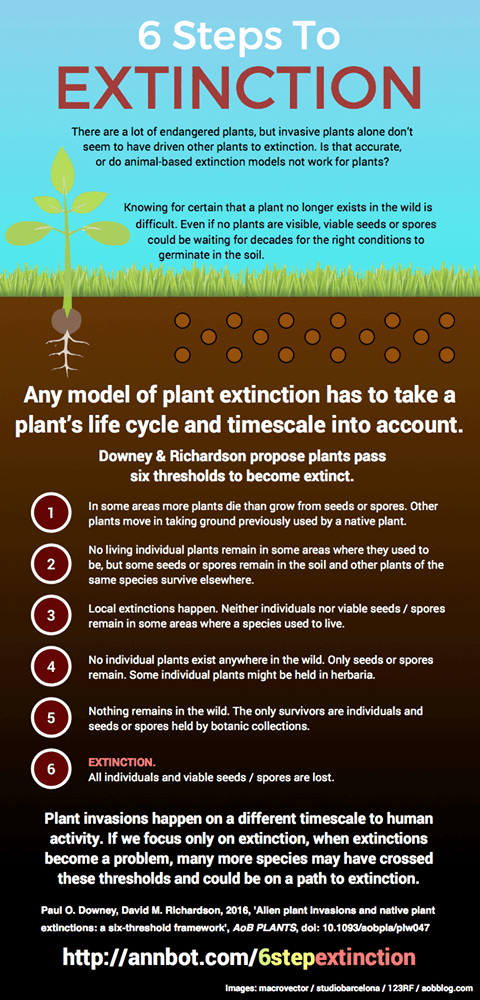

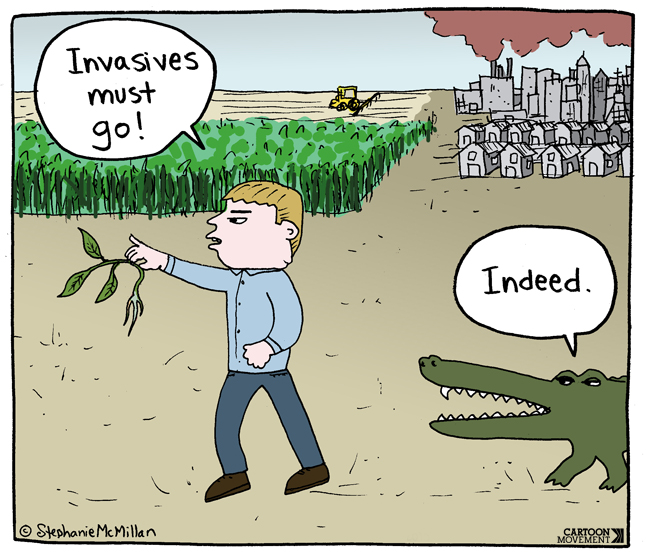

As humans move around the globe, they are regularly accompanied by plants. Some plant species are intentional guests, while others are interlopers. This steady movement of plants from one region to another results in plants being introduced to areas where they are not native. In this regard, they are aliens. Some of these alien species will take up permanent residence and, as a result, can disrupt ecosystems, compete with native plant species, and cause economic damage. This earns them the title “invasive”. But not all introduced plant species achieve this. In fact, many will find themselves in a new region but will be unable to colonize. Others will colonize but not become fully established. Still others become established but will not spread. In all cases there are factors at play that either aid or limit an introduced plant species in becoming invasive.

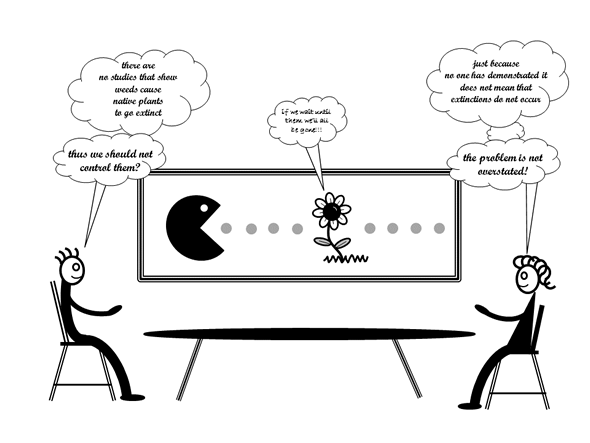

In a review published in New Phytologist (2007), Kathleen Theoharides and Jeffrey Dukes examine four stages of invasion (transport, colonization, establishment, and landscape spread) and some of the “filters” that occur in each stage that help determine whether or not an alien plant species will become invasive. In their introduction they clarify, “these stages are not discrete, and filters will likely affect more than one stage,” but by analyzing each of the stages we can better determine how and why some introduced species are successful at becoming invasive while others are not. Generalities derived from this investigation can “be used to predict the outcome of invasion events, or to explore mechanisms responsible for deviations from these generalizations.”

Theoharides, K. A. and Dukes, J. S. (2007), Plant invasion across space and time: factors affecting nonindigenous species success during four stages of invasion. New Phytologist, 176: 256–273. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02207.x

In part one, we will look at the first two stages of invasion: transport and colonization.

Species have always moved around from region to region by various means. However, as Theoharides and Dukes write, “current species movements are happening faster than before and from more distant regions, primarily as a result of global commerce and travel.” When it comes to human-mediated dispersal, many plants may never be transported by humans, while others simply won’t survive the journey. Species that are widespread may have a better chance of being transported because they are more likely to make contact with humans. Transporting high numbers of propagules (i.e. seeds, spores, cuttings) generally increases the likelihood that a species will survive the journey.

The invasion of Phalaris arundinacea (reed canary grass) was facilitated by multiple introduction events from a variety of sources within the native European range.” — Theoharides, K. A. and Dukes, J. S. (2007) [photo credit: eol.org]

Surviving transportation is not a guarantee that alien plants will successfully colonize a new area. Myriad environmental conditions and biological processes stand in their way. Much depends on propagule pressure – “the combined measure of the number of individuals reaching a new area in any one release event and the number of discrete release events.” Where propagule pressure is high, colonization is more likely. Repeated introductions across a large area offer the species a greater chance of finding itself in a suitable location as well as a greater level of genetic variation. Disturbed environments with less competitors and increased resources (i.e. light, moisture, soil nutrients) are often easier to colonize than locations with a high level of biodiversity and fewer available resources.

“Populations of Salix babylonica (weeping willow) in New Zealand may have invaded from a single cutting.” — Theoharides, K. A. and Dukes, J. S. (2007) [photo credit: eol.org]

If and when colonization is achieved, establishment is no guarantee. “In order for a plant to establish itself it must continue to increase from low density over the long term.” Small numbers of plants may successfully reproduce, but environmental factors, genetic issues, and biological competition may still stand in their way. Species that invade disturbed sites where resource availability is temporarily high, may soon find themselves in a resource-limited situation. As a result, their populations may dwindle.

With transport and colonization accomplished, establishment is the next goal. Establishment and landscape spread will be covered in part two.