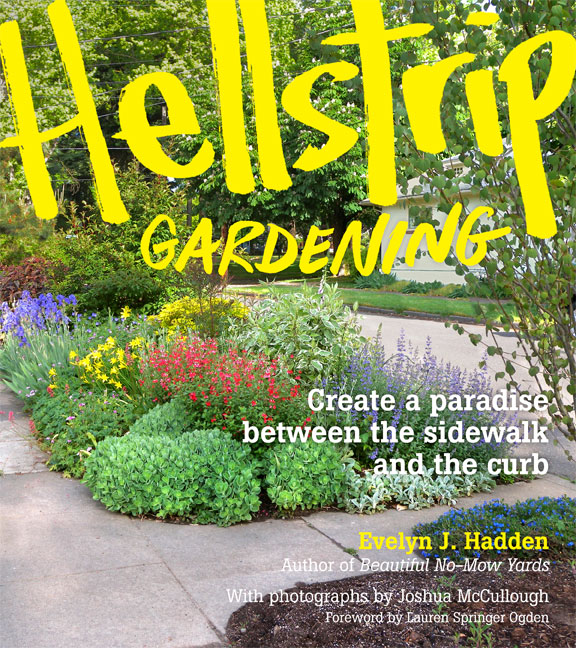

The second section of Evelyn J. Hadden’s book, Hellstrip Gardening, is all about the unique challenges and obstacles one faces when gardening in that stretch of land between the sidewalk and the road. I highlighted some of those challenges last week. This week we are into the third section of Hadden’s book, the part that is all about designing, building, and managing a curbside garden. As I have read through this book, I have begun to look at hellstrips in a much different light. They are no longer boring sections of yard with little potential, but instead are full of possibility and have unique characteristics involving publicity and functionality that are absent from most of the rest of the urban landscape. Now that we are in the creation phase of the book, this fact becomes abundantly clear.

Choosing a Style

When deciding how to design and plant your curbside bed, it is important to consider – along with aesthetics – the functions you wish to achieve (storm water runoff collection, food production, wildlife habitat, etc.) as well as how you are going to maintain it. You may decide to embrace minimal maintenance with a mass planting of a single species or mass plantings of a handful of species in sections called drifts. This can be very attractively done, but it also has the risk of a disease or pest wiping out a section of plants. A mass planting of ground covers acts as a living mulch and will eliminate the need to replenish non-living mulch. Hadden provides descriptions of a few styles of garden design, such as formal, naturalistic, cottage garden, and stroll garden, each with their virtues and limitations. Growing food is also an option in a hellstrip. If this is the option you choose, keep the bed looking full by intermixing flowers and crop plants, growing perennial crops, and staggering planting times. Ultimately the style of the garden is the preference of the gardener; however, the environmental conditions of the hellstrip must also be a consideration.

Choosing Plants

Because hellstrips are by nature public gardens, they are the ideal place for plants that appeal to the human senses – plants that invite interaction. Hadden calls these plants “friendly plants.” They are plants that are aromatic, have interesting textures and bold colors, “feel great underfoot,” have “aesthetically pleasing symmetry,” and have unusual flowers or unique foliage. Hadden asserts that, “plants that invite touching engender good will,” so consider the ways that your hellstrip might make you a better neighbor.

Their public nature also means that hellstrip gardens are not the place for rare and valuable plants, and instead are ideal for easily replaceable and self-repairing plants. This includes perennials that are easily divided, shrubs that reproduce by layering, creeping plants that send out runners, and plants with seeds that are easily collected and can be sown in bare spots. One option is to plant only annuals. This eliminates the loss of plants during the winter when snow, sand, and/or salt are deposited in the beds by road clearing equipment. Just be sure to protect the soil with mulch or a cover crop during the cold months of the year.

A hellstrip is also an ideal location for an alternative lawn. Traditional lawns require loads of water and fertilizer and regular mowing in order to stay looking good. There are lots of other grasses and ground covers available now that are drought tolerant, require little or no fertilizer, don’t need to be mowed often or at all, and are still very attractive. Hadden has a website all about lawn alternatives called Less Lawn.

The seed heads of blue grama grass (Bouteloua gracilis), one of many attractive alternatives to traditional turfgrass. (photo credit: www.eol.org)

When selecting plants for your hellstrip garden, consider the conditions it will have to endure. Unless you want to make serious amendments in order to accommodate certain plants, it is probably best to choose plants that are already adapted to your site. One way to determine this is to observe sites similar to yours and see what is thriving there; particularly make note of plants that look like they have been there for a while. Also, feel free to ask local experts at garden centers and public gardens what they might recommend for your site.

Earthshaping

“Diverse topography makes a more visually interesting garden, and it adds microclimates, letting you grow more diverse plants.” Shaping a curbside bed can also serve other functions such as softening traffic noise, defining pathways, collecting runoff, and providing wildlife habitat. When building a large berm, first create a rocky base and then fill in the spaces between the rocks with sand and small gravel. After that, add topsoil and firmly pack it down with machinery or a rolling drum. Small berms can be formed by simply piling up excess soil or turning over sections of sod and piling them up. Maintain good plant coverage on berms in order to reduce erosion, and consider planting shrubs with extensive root systems like sumac (Rhus sp.) and snowberry (Symphoricarpos sp.).

Hellstrips are ideal locations for rain gardens and bioswales since they are typically surrounded by impervious surfaces. Storm water can be directed from these surfaces into your rain garden, thereby reducing the amount of storm water runoff that must be handled elsewhere. Hadden provides a brief overview on how to construct a rain garden; the process is too detailed to go into here. If you are serious about building one, it is important to do your research beforehand to be sure that it is built properly. There are several great resources available; one that I would recommend is Washington State University Extension.

Partnering with Nature

Time spent managing and maintaining your hellstrip garden can be greatly reduced when it is well planned out, contains plants that are suited to the site, and has good soil health. Helping you achieve these things is essentially what Hadden’s book is all about. Watering properly and wisely is key to the success of your hellstrip garden. Hadden suggests organizing plants into “irrigation zones,” separating those that need little or no water from those that need frequent or regular watering. When you do water, water “thoroughly and infrequently to maximize deep root growth and drought resistance.” Consider installing a drip irrigation system, particularly one that will direct the water to the roots of the plants and deliver it slowly. Avoid watering areas where there are no plants, as this encourages weed growth.

Mostly likely you will be doing some amount of trimming and pruning in your hellstrip. Consider how you will handle this plant material. You may choose to cut it up into fine pieces and leave it as mulch; or maybe you have a compost pile to add to. Large woody materials can be placed in a section of your property set aside for wildlife habitat. Choosing plants that will not outgrow the space will reduce the amount of pruning you will need to do.

As much as Hadden is an advocate for alternatives to conventional lawns, she is also an advocate for reducing the use of gas-powered leaf blowers. Nobody enjoys hearing the clamor of a smelly, polluting leaf blower echoing through the neighborhood, so be a good neighbor and use a broom or rake instead. You will probably enjoy the task more as you listen to nature, get some exercise, and revel in your garden.

Continued focus on building healthy soil is paramount to the ongoing success of your curbside garden. Continue to add organic matter by letting some of the plant litter lie and decompose. Plant nitrogen fixing species like lupines (Lupinus sp.) and false indigos (Baptisia sp.). As much as possible avoid compacting the soil, especially when it is wet, and keep tilling and digging to a minimum once the garden is planted.

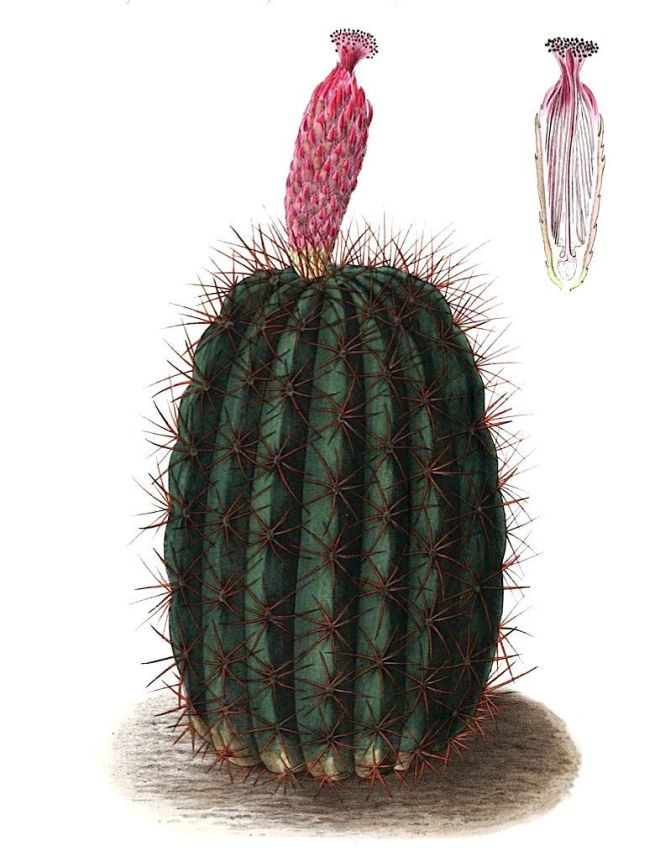

Partridge pea (Chamaecrista fasciculata), an annual plant in the pea family (Fabaceae). One of many nitrogen fixing plants that can help improve soil fertility. (photo credit: www.eol.org)

Again, this is only a fraction of what Hadden discusses in this section of her book. Consult the book for more of her wisdom. The final section of Hellstrip Gardening is a long list of plants that are “curbside-worthy” complete with photos and descriptions. Next week’s post will be all about a particular type of hellstrip garden that employs a subsection of those plants.