Always on the lookout for more podcasts to listen to, I somehow stumbled upon Native Plant Podcast. I wish I could remember the rabbit hole I went down that brought me to this masterpiece, but I can’t. What I do remember is being hesitant at first. I am all for calling things what they are. A restaurant called “Restaurant?” Why not? A podcast about native plants called “Native Plant Podcast?” Sure. It’s not the most creative name, but it works. What I was worried about, though, was that a podcast calling itself after native plants was going to be preachy, pushy…or just dull.

Yet I work with native plants every day(!), and I love them – so my initial judgement must say more about myself than anything else. Despite my hesitation – and my inclination to judge a podcast by its cover – I gave it a shot. I’m so glad that I did, because what I found was a highly informative show that is simultaneously delightful, fun, goofy, and entertaining. It’s a podcast that doesn’t take itself too seriously. The hosts and their guests share an important message about the benefits of native plant gardening, and they do so with passion and a sense of urgency while remaining lighthearted and approachable.

Native Plant Podcast is young. The first episode came out in January 2016. It is run by three individuals that met at the Cullowhee Native Plant Conference in North Carolina (a conference that is often mentioned on the podcast). Mike Berkeley and John Magee are the regular hosts; Jesse Turner mainly operates behind the scenes but makes appearances on a few episodes. They each have their own nursery and/or landscaping businesses that deal largely with native plants. Together they have decades of experience working with native plants. In an episode with Neil Diboll of Prairie Nursery, Mike makes the comment that they “were into native plants before it got cool.” Several of the guests that have been on the podcast so far can say the same thing.

One such guest is Miriam Goldberger, owner of Wildflower Farm and author of Taming Wildflowers, who appears on two episodes (part 1 and part 2). Other notable guests include Thomas Rainer, co-outhor of Planting in a Post-Wild World, and David Mizejewski, a naturalist for the National Wildlife Federation. So far all of the guests have been great, and since the the podcast has only been around for a few months, it is easy to catch up on past episodes.

As someone who enjoys sitting around talking about plants, this podcast is perfect since much of the “airtime” is taken up by such discussions. The episodes about winter interest and spring gardening are particularly great for this sort of thing. Two other standout episodes are the introductory episode, in which Mike and John discuss how they got started working with native plants, and the episode about defining native plants, in which Mike, John, and Jesse all take a crack at coming up with a definition. A topic that comes up often on the podcast is native plant cultivars (John understandably cringes each time he hears the portmanteau of “native” and “cultivar”), which seems to be a controversial topic in the native plant world.

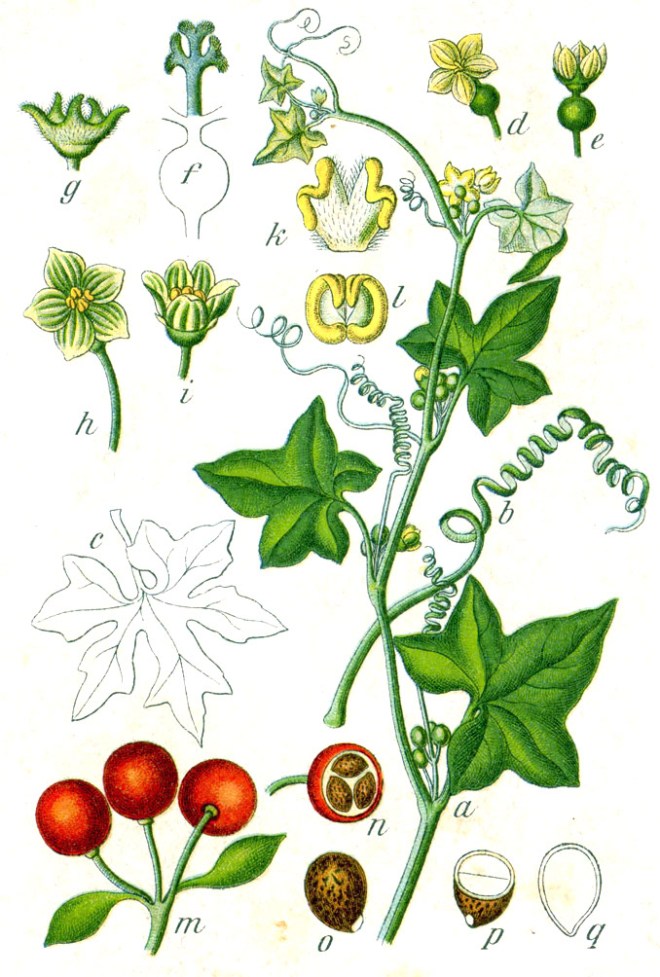

Prairie dropseed (Sporobolus cryptandrus) – one of Mike and John’s favorite grasses and a plant that comes up frequently on the podcast. (photo credit: wikimedia commons)

In each episode of the podcast there is an interview/discussion followed by three short segments: listener questions, stories about dogs or other pets (the hosts really love their dogs), and a toast (in which the hosts pop open their beers in front of the microphone for all to hear). The twitter bio for the Native Plant Podcast sums it up well: “A podcast started by a group of goofballs to highlight the beauty and functionality of native plants in the landscape.” These goofballs really know their stuff, and I highly recommend listening to their show.

Bonus quote from the episode with Neil Diboll:

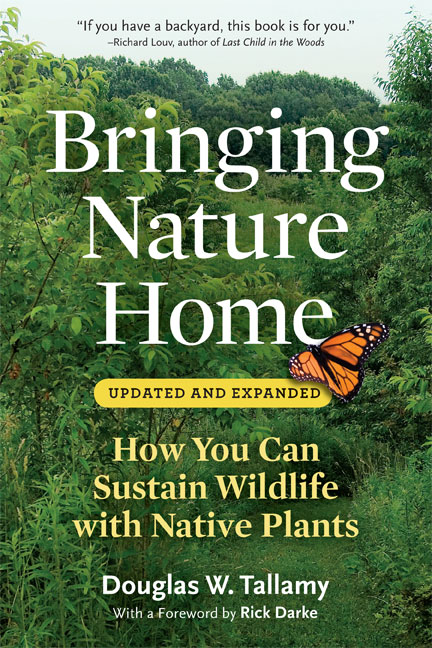

Everybody says they love Mother Nature, but if you look at people’s yards, very few people actually invite her over. Most people have lawns that are mown to within an inch or two of their lives, and the typical American garden is like a big pile of mulch with a few perennials stuck in it or maybe a few shrubs stuck in it. These are really non-functional gardens from a standpoint of an ecological approach, so bringing your landscaping to life is creating ecological gardens that are not just for the owner of the property, but for all life that you can attract to the land for which you are the steward.