This is a guest post by Laura-Marie River Victor Peace Nopales (see contact info below).

Hello! I made a guest post on Awkward Botany in March, introducing myself and my spouse, and talking a little about my life with permaculture. Permaculture is a way I learn about plants, love the earth, grow delicious foods, and connect with others. Permaculture has a community aspect, and respect for all beings is part of that. Permaculture is a great idea for disabled people.

Being disabled is a lot of work, and butting up against ableism all around is part of that. A default assumption many have, including many permaculture teachers, is that people are full of abundant energy and can live our values if we choose to. But being disabled means that what we want to do often isn’t the same as what we can accomplish. Disabled permaculture is a great take on permaculture that Ming and I have been doing together for 11 years of friendship and partnership.

Disabled permaculture is a valuable concept that many people can benefit from and customize to their own needs. Throughout this essay, I’ll mention many ways it helps me and Ming live a beautiful interdependent life.

how we’re disabled

My spouse Ming and I are both disabled. He has narcolepsy, so he falls asleep at unwanted times, doesn’t get restful sleep, and many aspects of life are impacted by his low energy and lack of wakeful cognition. Narcolepsy can contribute to struggles with memory, language, and reality comprehension. Ming also has a diagnosis of OCD.

Ming endures heartache trying to get his medical needs met, since a medication he uses for wakefulness is a controlled substance. The drug war plus health insurance nonsense means he has to jump through more hoops than anyone should need to, let alone a disabled person.

As for me, I have psychiatric diagnoses and hear voices, along with social differences and sensory sensitivities. Some terms that might apply to me are anxious and autistic. I like “crazy” as a reclaimed term, like queer and fat, which also apply. I have a schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type diagnosis. I was sedated on a bipolar cocktail for around 11 years.

how permaculture suits us

Permaculture is a helpful design system for disabled people such as ourselves. We have limited energy and fluctuating capabilities. Sometimes we’re not up for much. Permaculture is helpful as a realistic, forgiving, less energy intensive way of growing plants and doing community.

Permaculture is about working with the land forms and nature’s rhythms, not fighting against them. It’s observantly respectful to Mother Earth and one another.

A goal is to create food forests that are self-sustaining. We permaculturists like to take a long view, start small, design for resilience, and rest in hammocks. We create closed loop systems. It’s fun to consider the weaknesses of our systems’ interdependence and arrange backups for our backups, with layers of redundancy. Problems are seen as opportunities. We have a thing for hugelkultur. We enjoy rich diversity, especially at the edges.

Permaculturists love nourishing the land, with compost, generous mulching, water catchment in swales, and other ways of making the land more rich than the scraggly vacant lots and neglected yard space we arrived to. We like doing land justice, so inviting people in, opposing food deserts by sharing our bounty, organizing community gardens, and working together with locals.

We prefer collaboration over gentrification. Smiling, we get a lot of joy out of seed bombs, guerilla gardening wild areas, and having a lemonade party, when life gives us lemons and we make lemonade.

I’ve enjoyed gleaning fruit to share with Food Not Bombs, harvesting olives with neighbors, and lots of sheet mulching with discarded cardboard to unmake lawns. Permaculture has helped me by giving me a framework for the regenerative, earth-nourishing impulses that stirred within me already.

community and energy

If all of this sounds fun, that’s because it is. Why is permaculture especially good for people who are disabled?

Inviting people in and nourishing community means more people care about our garden, and are willing to step in when Ming and I are less out and about. Thank you to the kind community members who see what needs doing and are empowered to contribute to the thriving of garden life.

Also, permaculture is less energy intensive than other ways of growing plants. Long term solution is a relief. Food forests are like Eden. Creating and tending food forests means there can be a bit by bit accumulation of plants that work well together.

It’s not a stressful, all-at-once venture. There’s not the once or twice annual “rip everything out and start over” that I’ve seen other gardeners do. It feels relaxed and cumulative, good for a disabled pace.

When we have the energy and the weather is cooperative, we evaluate how the garden overall is doing. Do we have room for more herbs? Are enough flowers blooming to attract pollinators and keep them happy? What foods do we want to eat more of, in the next few months? Should we put sunflowers somewhere different this time? It’s unrushed, experimental, fun, and slow.

tree collards for disabled permaculture

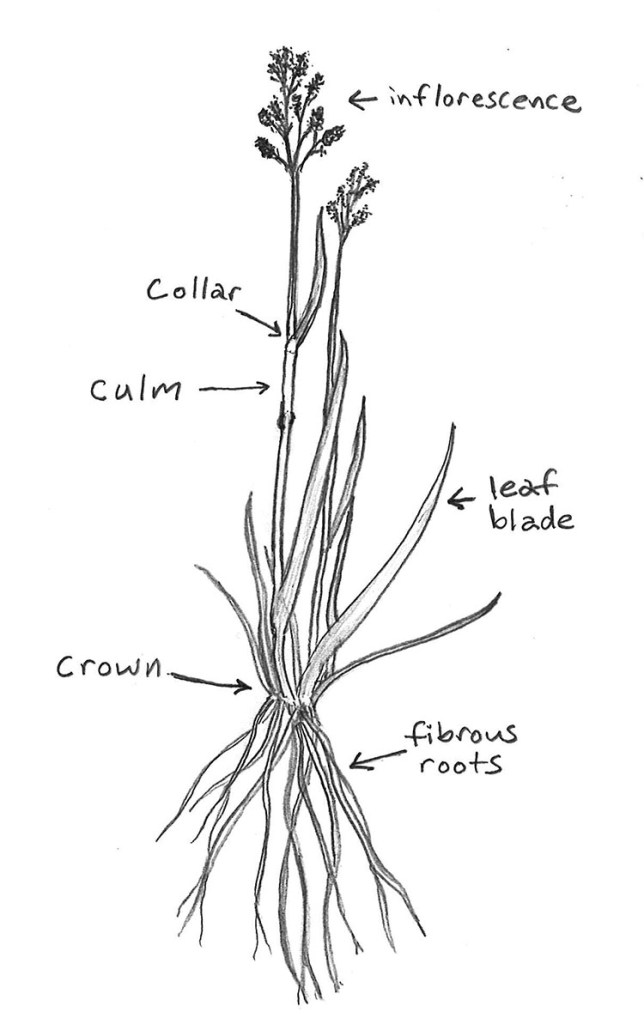

The tree collards I mentioned last post are easier to grow than regular collards and kale. Let me tell you about these delicious leafy brassicas as a disabled permaculture example. Tree collards give tasty greens perennially, for years. We get a lot of delicious food from them!

Tree collards are easy to propagate. No need to buy or save seeds, then tend tender seedlings. Just break off a branch, stick it in the garden ground, make sure it stays moist for a few weeks, and hope for the best. It may root and start growing soon.

The tree collards we have are purple with the green. They’re gorgeous and can get lush in the winter. They’re tasty by themselves, sautéed with garlic, added to beans. We had some on our Passover Seder plate recently. When I cook rice, I might add a few tree collard leaves at the end to steam and greenly compliment my carbs.

When I make pesto, I throw in a few leaves of tree collard with the basil. When Ming is gardening, he often munches a few leaves. I smell them, pungent on his breath, when he returns indoors and kisses me.

It’s fun to give cuttings to friends and share the bounty. We talk about perennial vs annual and biennial. We talk about permaculture as an important guiding force in our disabled family. Even if the cuttings die, ideas and love were propagated. By sharing our values, we’ve inviting them into our life.

I like watching tree collards age, lean over, flower, die back, surge forth, reach for the sun. We keep them in our permaculture zone 1, right by our front door, as they are our darlings. They’re available to us all the time.

inevitable

Many people are disabled one way or another, and many people will become disabled, if lucky enough to live into old age. Disabled permaculture is a way most anyone can garden. The investment can be small and gradual.

Some people think of gardening as expensive, requiring tools and the building of raised beds, remaking the garden seasonally, and the accumulation of books and arcane knowledge. But permaculture is humble, less expensive, and becomes an intuitive part of life.

Our garden is not a separate thing that we can choose to do or not do, this spring. It’s always happening, like the other aspects of our creativity, our health, our family, and the cycles of nature.

Laura-Marie River Victor Peace Nopales is a queer trikewitch who enjoys zines, ecstatic dance, and radical mental health. Find her at listening to the noise until it makes sense.