Some plants have native ranges that are so condensed that a single major disturbance has the potential to wipe them out of existence completely. They are significantly more vulnerable to change than neighboring plant species, and for this reason they often find themselves on endangered species lists. Zizania texana is one of those plants. Its range was never large to begin with, and due to increased human activity it now finds itself on the brink of extinction.

Zizania texana is one of three species of wild rice found in North America. The other two, Z. palustris and Z. aquatica, enjoy much broader ranges. Both of these species were once commonly harvested and eaten by humans. Today, Z. palustris is the most commercially available of the two. Commonly known as Texas wild rice, Z. texana, was not recognized as distinct from the other two Zizania species until 1932.

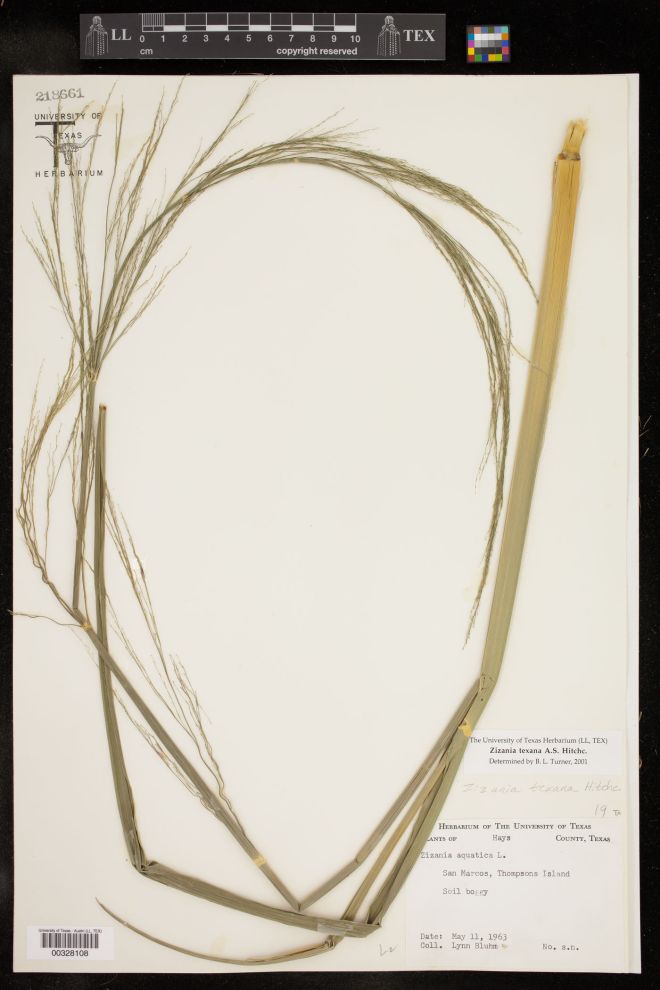

Herbarium voucher of Texas wild rice (Zizania texana) – photo credit: University of Texas Herbarium

Texas wild rice is restricted to the headwaters of the San Marcos River in Central Texas. The river originates from a spring that rises from the Edwards Aquifer. It is a mere 75 miles long, but is home to copious amounts of wildlife, including several rare and endangered species. Before the 1960’s, Texas wild rice was an abundant species found along several miles of the San Marcos River. Its population and range has since been greatly reduced, and the native population is now limited to about 1200 square meters within the first two miles of the river.

Texas wild rice is an aquatic grass with long, broad leaves that remains submerged in the clear, flowing, spring-fed water of the river until it is ready to flower. Flower heads rise above the water, and each flower spike consists of either male or female flowers. The flowers are wind pollinated, but research has revealed that the pollen does not travel far and does not remain viable for very long. If a male flower is further than about 30 inches away from a female flower, the pollen generally fails to reach the stigma. The plants also reproduce asexually by tillering, but plants produced this way are genetically identical to the parent plant.

As people settled in the area around San Marcos Springs and began altering the river for their own use, Texas wild rice had to put up with a series of assaults and dramatic changes, including increased sediment and nutrient loads, variations in water depth and speed, trampling, and mechanical and chemical removal of the plant itself. Sexual reproduction became more difficult. In his book, Enduring Seeds, Gary Paul Nabhan describes one scenario: “streamflow had been increased to the extent that the seedheads, which were formerly raised a yard above the water, [were] now constantly being pummeled by the current so that they [remained] submerged, incapable of sexual reproduction.”

San Marcos, Texas – where the headwaters of the San Marcos River is located and where Texas wild rice has long called its home – is the location of Texas State University and is part of the Greater Austin metropolitan area. Thus, Zizania texana now finds itself confined to a highly urbanized location. The San Marcos Springs and River are regularly used for recreation, which leads to increased sediments, pollution, and trampling. Introduced plant species compete with Texas wild rice, and introduced waterfowl and aquatic rodents consume it. In this new reality, sexual reproduction will remain a major challenge, and a return to its original population size seems veritably impossible.

Texas wild rice (Zizania texana) and its urbanized habitat – photo credit: The Edwards Aquifer

Attempts have and are being made to maintain the species in cultivation and to reintroduce it to its original locations, but its habitat has been so drastically altered that it will need constant management and attention for such efforts to be successful. As Nabham puts it, it is a species that has “little left of [its] former self in the wild – it is a surviving species in name more than in behavior…The wildness has been squeezed out of Texas rice.”

What if humans had stayed out of it? Would a plant with such a limited range and such difficulty reproducing sexually persist for any great length of time? It’s hard to say. If it disappears completely, what consequences will there be? It is known to provide habitat for the fountain darter, an endangered species of fish, as well as several other organisms; however, the full extent of its ecological role remains unclear. It will be nursed along by humans for the foreseeable future, but it may never regain its full glory. It is a species teetering on the edge of extinction, simultaneously threatened and cared for by humans – a story shared by so many other species around the world.

Additional Resources:

- Texas Parks and Wildlife: Texas Wild-rice

- Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center: Zizania texana

- You Tube: Texas Wild Rice – Center for Plant Conservation National Program Plant Profile

- Power, P. 1996. Growth of Texas wild rice (Zizania texana) in three sediments from the San Marcos River. Journal of Aquatic Plant Management 34: 21-23.

- Assessment of factors influencing Texas wild-rice (Zizania texana) sexual and asexual reproduction: 2004 Final Report by Paula Power and F.M. Oxley