When I began this series of posts, I didn’t have a clear vision of what it would be. I had a budding interest in pollination biology and was anxious to learn all that I could. I figured that calling 2015 the “Year of Pollination” and writing a bunch of pollination-themed posts would help me do that. And it has. However, now that the year is coming to a close, I realize that I neglected to start at the beginning. Typical me.

What is pollination? Why does it matter? The answers to these questions seemed pretty obvious; so obvious, in fact, that I didn’t even think to ask them. That being said, for these last two “Year of Pollination” posts (and the final posts of the year), I am going back to the basics by defining pollination and exploring some of the terms associated with it. One thing is certain, there is still much to be discovered in the field of pollination biology. Making those discoveries starts with a solid understanding of the basics.

Pollination simply defined is the transfer of pollen from an anther to a stigma or – in gymnosperms – from a male cone to a female cone. Essentially, it is one aspect of plant sex, albeit a very important one. Sexual reproduction is one way that plants multiply. Many plants can also reproduce asexually. Asexual reproduction typically requires less energy and resources – no need for flowers, pollen, nectar, seeds, fruit, etc. – and can be accomplished by a single individual without any outside help; however, there is no gene mixing (asexually reproduced offspring are clones) and dispersal is limited (consider the “runners” on a strawberry plant producing plantlets adjacent to the mother plant).

To simplify things, we will consider only pollination that occurs among angiosperms (flowering plants); pollination/plant sex in gymnosperms will be discussed at another time. Despite angiosperms being the youngest group of plants evolutionarily speaking, it is the largest group and thus the type we encounter most.

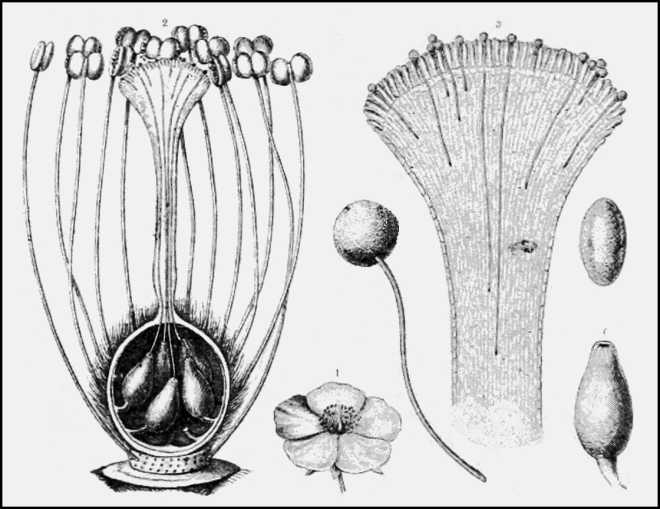

A flower is a modified shoot and the reproductive structure of a flowering plant. Flowers are made up of a number of parts, the two most important being the reproductive organs. The androecium is a collective term for the stamens (what we consider the male sex organs). A stamen is composed of a filament (or stalk) topped with an anther – where pollen (plant sperm) is produced. The gynoecium is the collective term for the pistil (what we consider the female sex organ). This organ is also referred to as a carpel or carpels; this quick guide helps sort that out. A pistil consists of the ovary (which contains the ovules), and a style (or stalk) topped with a stigma – where pollen is deposited. In some cases, flowers have both male and female reproductive organs. In other cases, they have one or the other.

When pollen is moved from an anther of one plant to a stigma of another plant, cross-pollination has occurred. When pollen is moved from an anther of one plant to a stigma of the same plant, self-pollination has occurred. Cross-pollination allows for gene transfer, and thus novel genotypes. Self-pollination is akin to asexual production in that offspring are practically identical to the parent. However, where pollinators are limited or where plant populations are small and there is little chance for cross-pollination, self-pollination enables reproduction.

Many species of plants are unable to self-pollinate. In fact, plants have evolved strategies to ensure cross-pollination. In some cases, the stamens and pistils mature at different times so that when pollen is released the stigmas are not ready to receive it or, conversely, the stigmas are receptive before the pollen has been released. In other cases, stigmas are able to recognize their own pollen and will reject it or inhibit it from germinating. Other strategies include producing flowers with stamens and pistils that differ dramatically in size so as to discourage pollen transfer, producing separate male and female flowers on the same plant (monoecy), and producing separate male and female flowers on different plants (dioecy).

As stated earlier, the essence of pollination is getting the pollen from the anthers to the stigmas. Reproduction is an expensive process, so ensuring that this sex act takes place is vital. This is the reason why flowers are often showy, colorful, and fragrant. However, many plants rely on the wind to aid them in pollination (anemophily), and so their flowers are small, inconspicuous, and lack certain parts. They produce massive amounts of tiny, light-weight pollen grains, many of which never reach their intended destination. Grasses, rushes, sedges, and reeds are pollinated this way, as well as many trees (elms, oaks, birches, etc.) Some aquatic plants transport their pollen from anther to stigma via water (hydrophily), and their flowers are also simple, diminutive, and produce loads of pollen.

Inflorescence of big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), a wind pollinated plant – photo credit: wikimedia commons

Plants that employ animals as pollinators tend to have flowers that we find the most attractive and interesting. They come in all shapes, sizes, and colors and are anywhere from odorless to highly fragrant. Odors vary from sweet to bitter to foul. Many flowers offer nectar as a reward for a pollinator’s service. The nectar is produced in special glands called nectaries deep within the flowers, inviting pollinators to enter the flower where they can be dusted with pollen. The reward is often advertised using nectar guides – patterns of darker colors inside the corolla that direct pollinators towards the nectar. Some of these nectar guides are composed of pigments that reflect the sun’s ultraviolet light – they are invisible to humans but are a sight to behold for many insects.

In part two, we will learn what happens once the pollen has reached the stigma – post-pollination, in other words. But first, a little more about pollen. The term pollen actually refers to a collection of pollen grains. Here is how Michael Allaby defines “pollen grain” in his book The Dictionary of Science for Gardeners: “In seed plants, a structure produced in a microsporangium that contains one tube nucleus and two sperm nuclei, all of them haploid, enclosed by an inner wall rich in cellulose and a very tough outer wall made mainly from sporopollenin. A pollen grain is a gametophyte.”

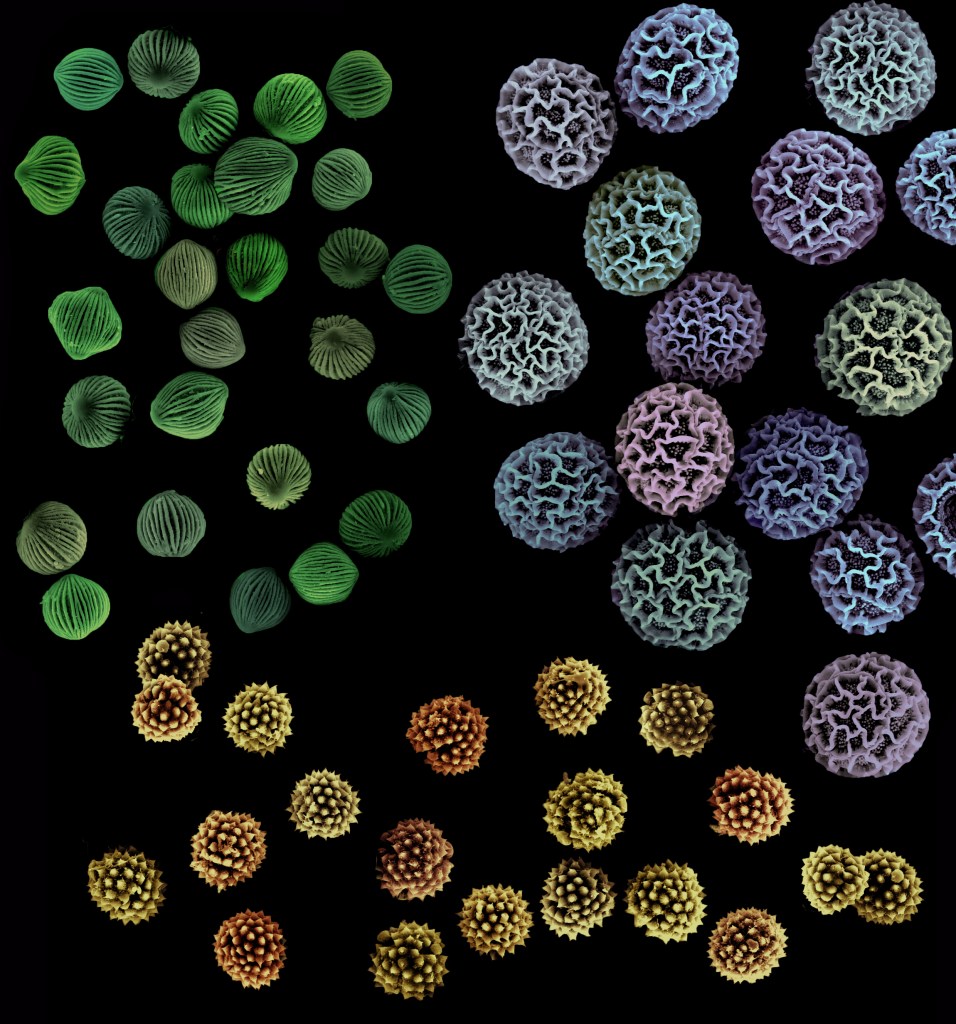

A pollen grain’s tough outer wall is called exine, and this is what Allaby has to say about that: “It resists decay, and the overall shape of the grain and its surface markings are characteristic for a plant family, sometimes for a genus or even a species. Study of pollen grains preserved in sedimentary deposits, called palynology or pollen analysis, makes it possible to reconstruct past plant communities and, therefore, environments.”

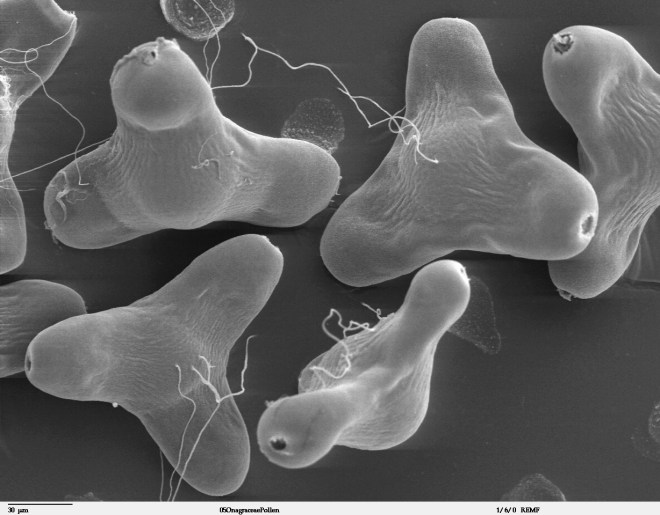

Scanning electron microscope image of pollen grains from narrowleaf evening primrose (Oenothera fruticosa) – photo credit: wikimedia commons