Prunella vulgaris can be found all over the place. It has also been used to treat just about everything. What else would you expect from a plant known commonly as self-heal, heal-all, all-heal, and woundwort? The medicinal value of this plant has been appreciated for centuries across its expansive range, and studies evaluating its medicinal use continue today. Being such a ubiquitous species – both as a garden plant and a native plant (and also a common weed) – and because it has so much clout in the world of herbal medicine, it’s an obvious candidate for Tea Time.

Self-heal is a member of the mint family (Lamiaceae), easily distinguished by its square stems, opposite leaves, and bilabiate and bilaterally symmetrical (or zygomorphic) flowers. One surprise is that, unlike the many aromatic members of this family, the foliage of self-heal lacks a strong scent. P. vulgaris occurs naturally across Asia, throughout Europe, and in parts of northern Africa. It is also widely distributed across North America. Apart from that, it has been introduced to many regions in the southern hemisphere and has also been frequently moved around throughout its native range. Eurasian varieties now intermingle with North American varieties, which can make it difficult to determine a native individual from an introduced one.

Self-heal is an adaptable plant that tends to prefer shady, moist locations, but can also be found in open, dry, sunny sites. Find it along forest edges, roadsides, ditches, and trails, as well as on the banks of streams, lakes, and reservoirs. It occurs in gardens, both intentionally planted and as a weed, and can escape into lawns, vacant lots, and open fields, as well as into nearby natural areas.

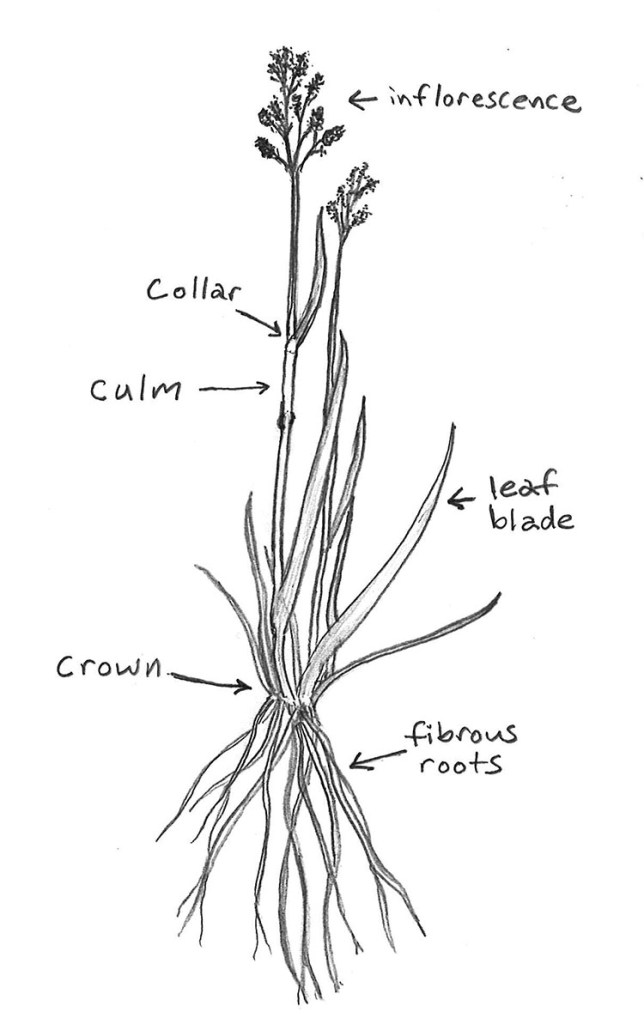

P. vulgaris is an evergreen that grows both prostrate and upright, sometimes reaching 1 foot tall or more (but is often much shorter). It has shallow, fibrous roots, and its stems root adventitiously as they sprawl across the ground, frequently forming an extensive mat or groundcover. Its leaves are oval to lance-shaped and measure about one inch long. Lower leaves have petioles, while upper leaves may become stalkless. Leaf margins are entire or can be slightly toothed. As plants age, they can develop a coppery or purple-bronze color.

The flowers of self-heal are generally a shade of purple, but can also be white, pink, or blue. They bloom irregularly in a spike measuring up to two inches long. Flower spikes are thick, dense, cylindrical, and made up of whorls of sharp-pointed bracts. Flowers bloom irregularly along the spike and occur from late spring/early summer into the fall. Each flower produces four nutlets, which sit within a cup-shaped, purple calyx.

As a medicinal herb, self-heal has been used both internally and externally to treat a long list of ailments. These include sore throats, diarrhea, fevers, intestinal infections, liver problems, migraines, heart issues, dermatitis, goiter, and thyroid disfunction, just to name a few. It has been used topically to treat skin irritations, bites, stings, and minor cuts and scrapes. This is thanks to its antimicrobial properties and its ability to stop bleeding. A report in the journal Pharmaceuticals (2023) calls P. vulgaris an “important medicinal plant” due to its “rich chemical composition” and its “pharmacological action.” Chemical analyses find the plant to be a valuable source of phenolic compounds, flavonoids, rosmarinic acid, and ursolic acid, among numerous other compounds. If you are curious to learn more detailed information regarding this plant’s medicinal value, you can refer to the above report, as well as one found in Frontiers in Pharmacology (2022).

P. vulgaris is an edible plant, and its young leaves can be eaten raw or cooked. The leaves together with the flowers can also be dried and used to make a tea. This is how I had it. I used about two teaspoons of dried leaves to one cup of water. Feel free to use more if you would like. I thought the tea was pretty mild. It had a slight sweetness to it and a hint of mint flavor. It has been described as bitter, but I didn’t find it to be overly so (although I may have a higher tolerance for bitterness). Sierra tried it and said that it tasted like “water left over from something else.” That might be because it was more diluted than she would have preferred. Overall, I thought it was a pleasant experience and would be happy to drink it again.