Plants that are otherwise perfectly edible can still find a way to kill you. That seems to be the lesson behind phytobezoars. A bezoar is a mass of organic or inorganic material found trapped in the gastrointestinal tract of animals. Bezoars are categorized according to the material they are composed of, so one composed of indigestible plant material is known as a phytobezoar. After learning about bezoars of all kinds on a recent episode of Sawbones, I decided a post about them was in order.

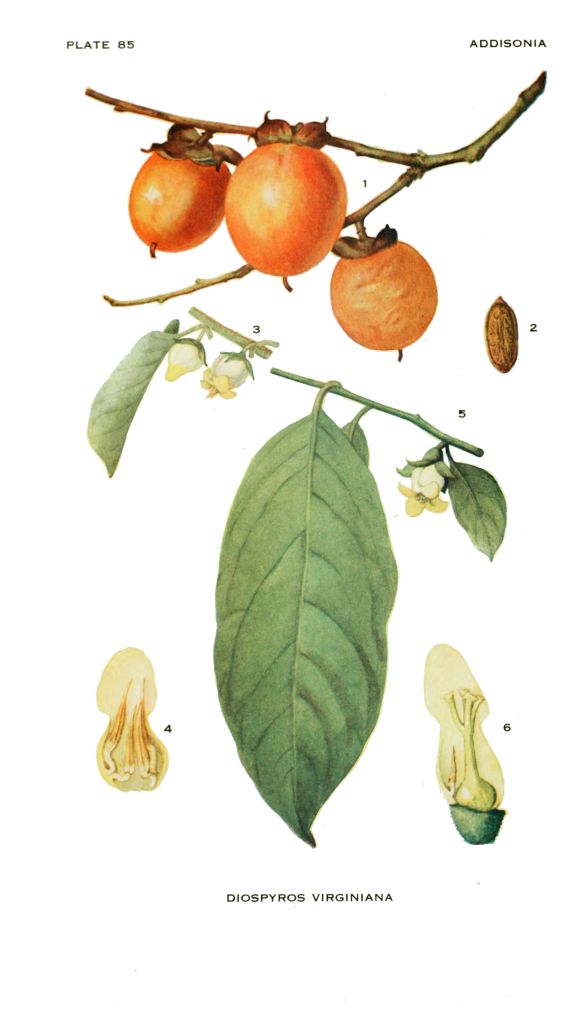

I was particularly intrigued by a very specific type of bezoar known as a diospyrobezoar, a subtype of phytobezoars that can result from eating large quantities of persimmons. The skins of persimmons (Diospyros spp.) are high in tannins. When the tannins mix with stomach acids, a glue-like substance forms and can lead to the creation of a diospyrobezoar.

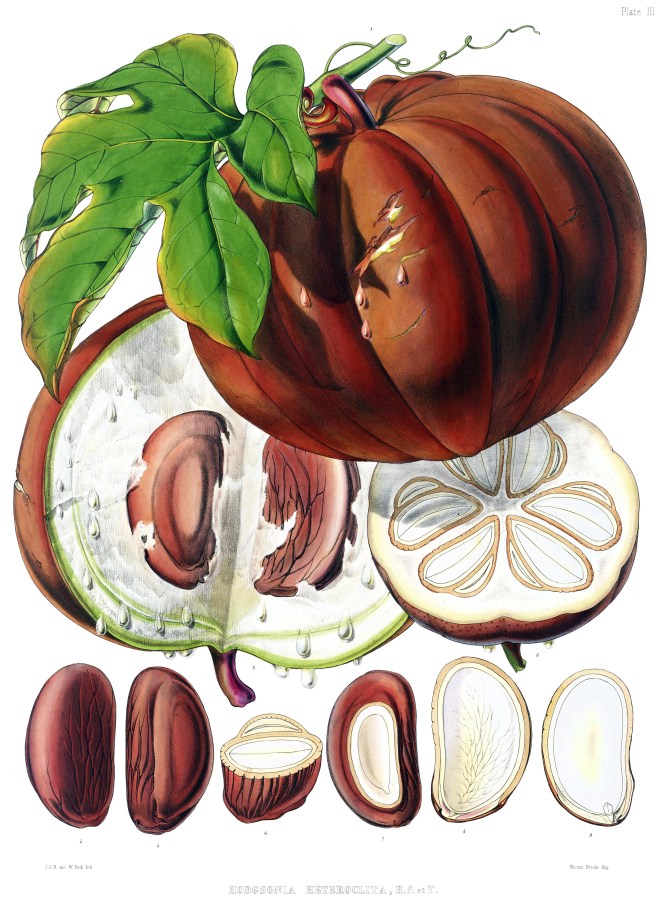

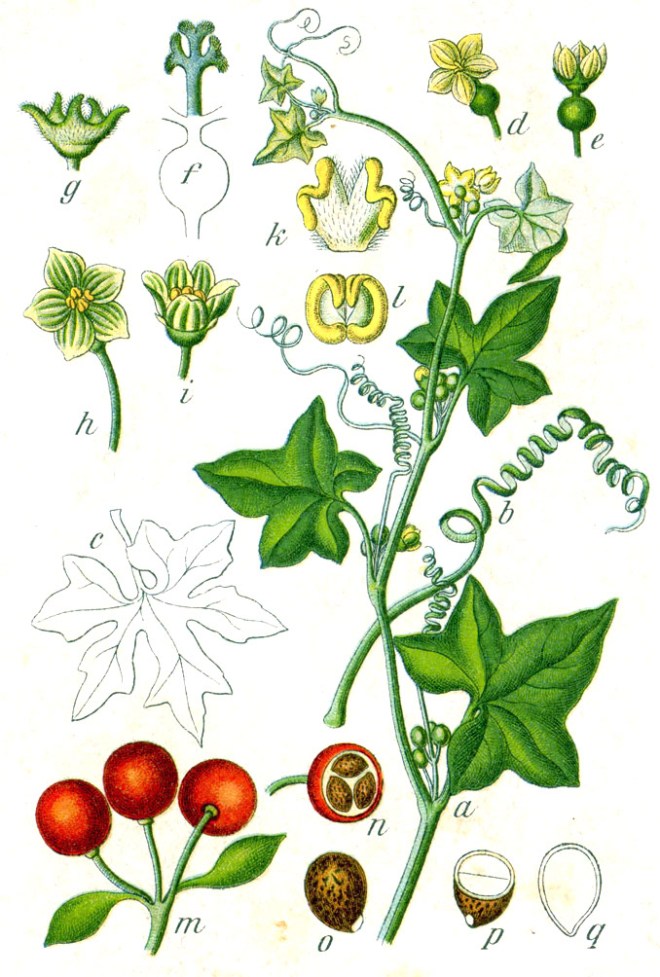

Fruits of Japanese persimmon (Diospyros kaki) – photo credit: wikimedia commons

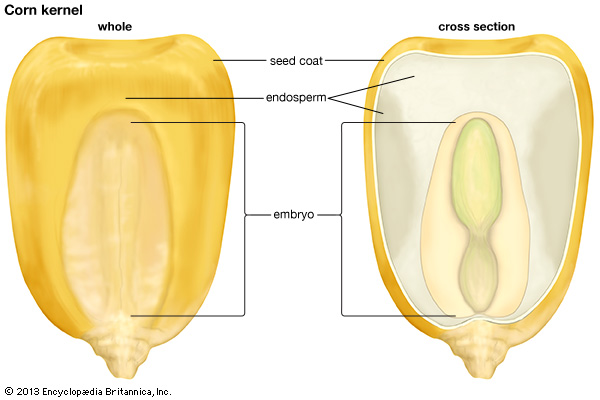

Phytobezoars are the most common type of bezoar and are generally composed of indigestible fibers, such as cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and tannins that are found in the skins of fruits and other plant parts. In general, phytobezoars are a rare phenomenon. The risk of obtaining them is higher in people who engage in certain activities (like consuming excessive amounts of high fiber foods or not chewing food properly) or who have certain medical conditions/have undergone certain medical treatments.

A study published in 2012 in Case Reports in Gastroenterology describes a specific incident involving the diagnosis and treatment of a diospyrobezoar. [It also includes a great overview of bezoars and phytobezoars if you feel like navigating through the sea of medical jargon]. The patient was a diabetic man in his 60’s that reported 5 days of abdominal pain after “massive ingestion of persimmons,” although it is not made clear what is meant by “massive” or “excessive” persimmon ingestion. Fourteen years prior, the patient had “undergone hemigastrectomy and associated truncal vagotomy to treat a chronic duodenal ulcer.” After a series of tests and observations, doctors determined that a large bezoar was lodged in the man’s intestines. Surgery was required to remove it. The recovered diospyrobezoar measured 12 cm x 5 cm and weighed 40 grams. Photos are included in the report if you must see them.

The authors of this study cite previous gastric surgery as being commonly associated with diospyrobezoar formation. They also cite previous abdominal surgery and absence of teeth as “predisposing factors.” They list major symptoms of bezoars, which include abdominal pain, bloating, vomiting and nausea, and small bowel obstruction. Phytobezoars most commonly form in the stomach where they can “generate gastric ulcers.” As you might imagine, the situation worsens if the phytobezoar enters the small intestine. Read the study for a more colorful description regarding that.

Surgery was necessary in this case, but not in all cases. The authors describe various medical and endoscopic treatments as alternatives to surgery. One approach is to try dissolving the bezoar using certain enzymes or Coca-Cola. The authors state that “there are several publications describing the successful use of Coca-Cola in treating bezoars.” [Here is a link to one such study.] The phosphoric acid and the carbon dioxide bubbles are suspected to be the active agents in breaking down the intruding masses. The authors warn, though, that “partial dissolution of bezoars located in the stomach can cause them to migrate to the small bowel, resulting in intestinal obstruction.”

Diospyrobezoars aside, persimmons are beautiful trees with lovely fruit. They are not out to get you any more than any other living organism out there, but their fruit should be consumed with caution. As with anything, the dose makes the poison. In the Sawbones episode, Sydnee McElroy specifically advises listeners to avoid unripe persimmons. That being said, the moral of the story is: if you like persimmons, eat them sparingly and make sure they’re ripe.

Want to learn more about persimmons and bezoars? Visit persimmonpudding.com for an excellent summary and lots of additional resources.

Common Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) is native to North America. According to the U.S. Forest Service it is “distributed from southern Connecticut and Long Island, New York to southern Florida. Inland it occurs in central Pennsylvania, southern Ohio, southern Indiana, and central Illinois to southeastern Iowa; and southeastern Kansas and Oklahoma to the Valley of the Colorado River in Texas.” – photo credit: eol.org