This a guest post. Words and photos by Jeremiah Sandler.

These notes do not discuss either anatomy or medicinal uses of Equisetum. Both topics are worthy of their own discourse.

Plants in the genus Equisetum can be found on each continent of our planet, except for Antarctica. The plants are collectively referred to as scouring rush or horsetail. Equisetum is in the division of plants called Pteridophytes, which contains all of the ferns and fern-allies (lycopods, whisk ferns, etc.) Pteridophytes are characterized by having a vascular system and by reproducing with spores, rather than seeds. Equisetum is the only living genus within the entire class Equisetopsida. Within this single genus, there are a mere 20 species.

Equisetums can live pretty much anywhere. They can tolerate lots of shade, lots of sun, and virtually any soil condition (including submerged soil). Rhizomatous stems make it difficult for either disease or insects to kill an entire population. They do not require pollinators because they reproduce with spores. Sounds like a recipe for reproductive and evolutionary success. Yet with all of these traits working in their favor, there is only a single genus left.

Where’d they all go?

Let’s briefly consider the origin of these plants first. In the late Paleozoic Era, during the end of the Cambrian Period, these plants began their takeover. Shortly thereafter (about 70 million years later), in the Devonian Period, land plants began to develop a tree-like habit, also called “arborescence.” Tree-sized ferns and fern-allies ruled the planet. They formed the ancient forests.

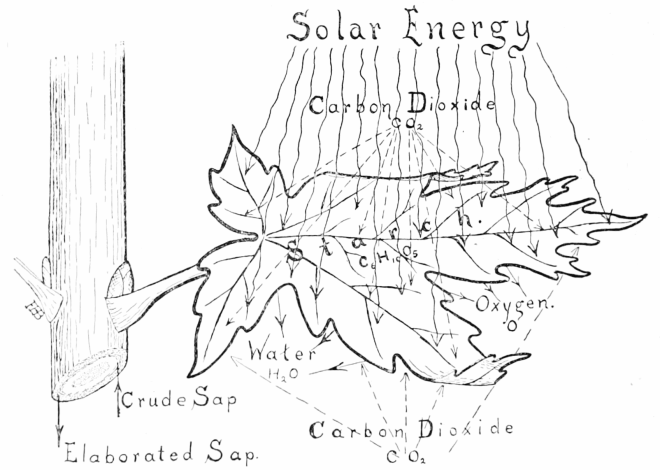

The elements required for photosynthesis were plentiful. The planet was warm. Competition from the Cambrian Explosion of flora and fauna drove plants upwards towards the sky. Larger plants can both shade their competition and remain out of reach of herbivores. None of the Equisetum species alive today are near their ancestors’ height.

It is rather obvious why we don’t see as many Equisetum species, and why they are not as large: The planet now is not the same planet it once was. Oxygen levels back in those times were about 15% higher than today’s levels. Seed plants can diversify much faster than non-seed-bearing plants; Equisetum cannot compete with the rate of diversification of seed-bearing plants.

The most interesting predicament comes when Equisetum is compared with other Pteridophytes. Some ancient Pteridophytes still do have diversity of genera. True Ferns, as they’re called, are broad-leaved ferns. In the class Filicopsida, there are 4 orders of True Ferns containing about 100 genera combined. Equisetum has 1 order and 1 genera.

What’s the primary difference between these two classes of Pteridophytes? Broad leaves.

Most pteridophytes tolerate some shade; most other plants can’t tolerate as deep of shade as ferns. More specifically, the amount of shade the plants create could be a deciding factor in this question. True ferns have all of the traits equisetums have, with one additional physical trait that has pulled them ahead: Broad leaves allow true ferns to actively shade out local competition while creating more habitat for themselves. Equisetums don’t have this aggressive capacity.

Of course there are other biological and evolutionary pressures affecting equisetums beside their lack of broad leaves. The structure they do possess has benefited them at a time when it was advantageous to have it. Otherwise why would it exist? Equisetums remind me of the dynamic nature of a planet. I don’t anticipate equisetums coming back.

Although, I find it entertaining to humor the idea that they might return to their former glory. The planet’s climate could change toward any direction (I’m not a climatologist, though). Maybe equisetums are adequately prepared to adapt to whatever changes come – or maybe we are observing the gradual decline of an old branch on the tree of life.