“Plantains – Plantago major – seem to have arrived with the very first white settlers and were such a reliable sign of their presence that the Native Americans referred to them as ‘white men’s footsteps.'” – Elizabeth Kolbert (The Sixth Extinction)

“Our people have a name for this round-leafed plant: White Man’s Footstep. Just a low circle of leaves, pressed close to the ground with no stem to speak of, it arrived with the first settlers and followed them everywhere they went. It trotted along paths through the woods, along wagon roads and railroads, like a faithful dog so as to be near them.” – Robin Wall Kimmerer (Braiding Sweetgrass)

photo credit: wikimedia commons

Plantago major is in the family Plantaginaceae – the plantain family – a family that consists of at least 90 genera, several of which include common species of ornamental plants such as Veronica (speedwells), Digitalis (foxgloves), and Antirrhinum (snapdragons). The genus Plantago consists of around 200 species commonly known as plantains. They are distributed throughout the world in diverse habitats. Most of them are herbaceous perennials with similar growth habits, and many have ethnobotanical uses comparable to P. major.

Originating in Eurasia, P. major now has a cosmopolitan distribution. It has joined humans as they have traveled and migrated from continent to continent and is now considered naturalized throughout most temperate and some tropical regions. In North America, P. major and P. lanceolata are the two most common introduced species in the Plantago genus. P. major has a plethora of common names – common plantain being the one that the USDA prefers. Other names include broadleaf plantain, greater plantain, thickleaf plantain, ribgrass, ribwort, ripplegrass, and waybread. Depending on the source, there are various versions of the name white man’s foot, and along the same line, a common name for P. major in South Africa is cart-track plant.

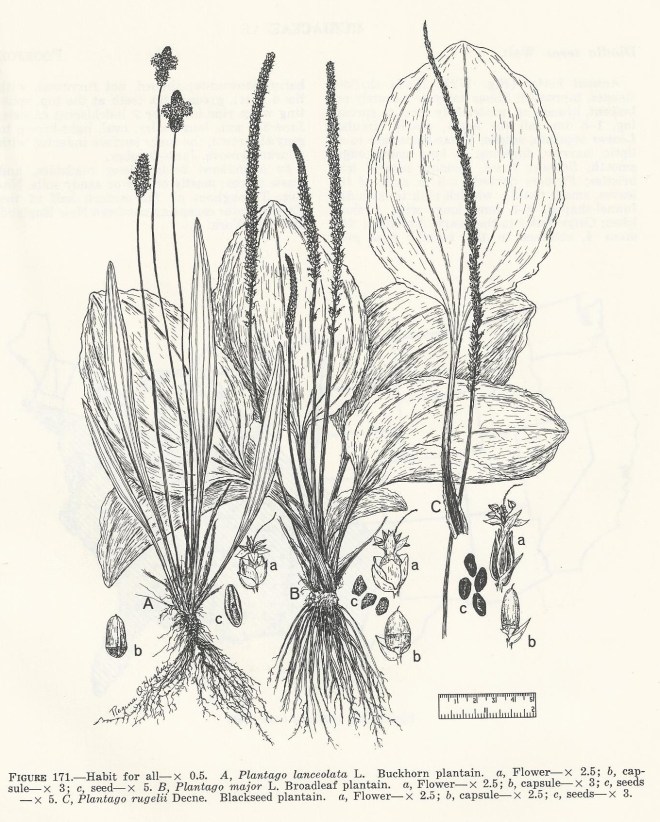

P. major is a perennial – albeit sometimes annual or biennial – herbaceous plant. Its leaves form a rosette that is usually oriented flat against the ground and reaches up to 30 cm wide. Each leaf is egg-shaped with parallel veins and leaf margins that are sometimes faintly toothed. The inflorescence is a leafless spike up to 20 cm tall (sometimes taller) with several tiny flowers that are a dull yellow-green-brown color. The flowers are wind pollinated, and the plants are highly prone to self-pollination. The fruits are capsules that can contain as many as 30 seeds – an entire plant can produce as many as 14,000 – 15,000 seeds at once. The seeds are small, brown, sticky, and easily transported by wind or by adhering to shoes, clothing, animals, and machinery. They require light to germinate and can remain viable for up to 60 years.

An illustration of three Plantago species found in Selected Weeds of the United States – Agriculture Handbook No. 366 circa 1970

P. major prefers sunny sites but can also thrive in part shade. It adapts to a variety of soil types but performs best in moist, clay-loam soils. It is often found in compacted soils and is very tolerant of trampling. This trait, along with its low-growing leaves that easily evade mower blades, explains why it is so commonly seen in turf grass. It is highly adaptable to a variety of habitats and is particularly common on recently disturbed sites (natural or human caused) and is an abundant urban and agricultural weed.

Even though it is wind pollinated, its flowers are visited by syrphid flies and various bee species which feed on its pollen. Several other insects feed on its foliage, along with a number of mammalian herbivores. Cardinals and other bird species feed on its seeds.

Humans also eat plantain leaves, which contain vitamins A, C, and K. Young, tender leaves can be eaten raw, while older leaves need to be cooked as they become tough and stringy with age. The medicinal properties of P. major have been known and appreciated at least as far back as the Anglo-Saxons, who likely used a poultice made from the leaves externally to treat wounds, burns, sores, bites, stings, and other irritations. Native Americans, after seeing the plant arrive with European settlers, quickly learned to use the plant as food and medicine. It could be used to stop cuts from bleeding and to treat rattlesnake bites. Apart from external uses, the plant was used internally as a pain killer and to treat ulcers, diarrhea, and other gastrointestinal issues.

P. major has been shown to have antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and other biological properties; several chemical compounds have been isolated from the plant and deemed responsible for these properties. For this reason, P. major and other species of Plantago have been used to treat a number of ailments. The claims are so numerous and diverse that it is worth exploring if you are interested. You can start by visiting the following sites:

- Encyclopedia of Life: Plantago major

- Invasive Species Compendium: Plantago major

- Plants for a Future: Plantago major

“White man’s footstep, generous and healing, grows with its leaves so close to the ground that each step is a greeting to Mother Earth.” – Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (photo credit: www.eol.org)