This is a guest post. Words and images by Jeremiah Sandler

———————

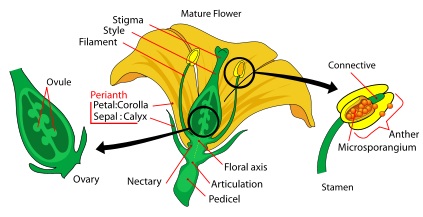

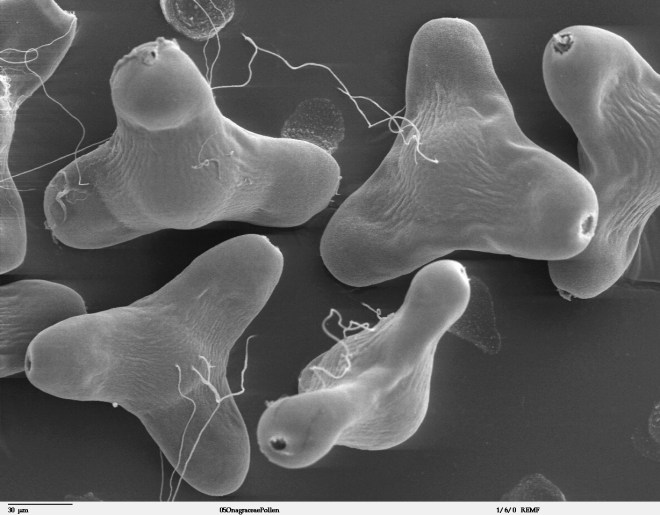

If you live in North America or Europe, chances are you have seen Dipsacus fullonum, commonly called teasel. Its tall (up to 2 meters), spiky flower stalks with large purple flowers are easy to spot in low-lands, ditches, or along highways. Since this prolific seeder’s introduction to North America from Europe, it has steadily increased its habitat to occupy nearly each region of the United States. Of course, like all plants, teasel has its preferences and is more frequent in some areas than in others.

Teasel is an unassuming, herbaceous biennial. It takes two years to complete its life cycle: First-year growth is spent as a basal rosette, and second-year growth is devoted to flowering. Standard biennial, right? As of 2011, an experiment was conducted on this plant that changed the way we see teasel, and possibly all other similar plants.

“Here we report on evidence for reproductive benefits from carnivory in a plant showing none of the ecological or life history traits of standard carnivorous species.” -Excerpt from the report titled Carnivory in the Teasel Dipsacus fullonum — The Effect of Experimental Feeding on Growth and Seed Set by Peter J.A. Shaw and Kyle Shackleton.

We all have favorite carnivorous plants, Venus flytraps, pitcher plants, sundews, etc.. Their showy traps and various means of attracting insects are all marvels of evolution in the plant kingdom. These insectivorous plants evolved these means of nutrient acquisition in an answer to the lack of nutrients in their environment’s soil. In some of these plants, there is a direct relationship between number of insects consumed and the size of the entire plant. In others, there is no such relationship.

The unassuming, biennial teasel can now join the ranks of carnivore, or protocarnivore. It didn’t evolve in bogs or swamps where soil nutrients are depleted. It has no relationship to the standard carnivorous species. It doesn’t have any flashy traps. In fact, it has no obvious traits which suggest it can gain nutrients from insects. Teasel’s carnivorous habits can be likened somewhat to the carnivorous habits of bromeliads; water gathered in their leaves traps insects.

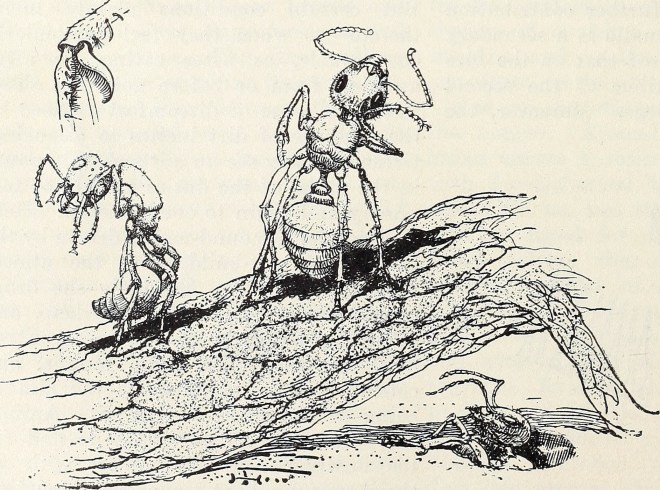

In Shaw and Shackleton’s experiment (done in two field populations), maggots were placed in water gathered in the center of some first-year rosettes of teasel. Other rosettes in the same population were left alone as controls. Not surprisingly, the teasels which were ‘fed’ larvae did not change in overall size. The size of the overwintering rosette did not offer any predictability towards the size of flower shoots for the coming year. However, something strange did happen:

“…addition of dead dipteran larvae to leaf bases caused a 30% increase in seed set and the seed mass:biomass ratio.”…“These results provide the first empirical evidence for Dipsacus displaying one of the principal criteria for carnivory”

Teasel has some physiology to absorb nutrients from other macroorganisms despite teasel evolving in an entirely different setting than typical carnivorous plants. Teasel’s already proficient reproductive capacity is enhanced by using insects as a form of nutrients in a controlled setting.

Many exciting questions have been raised by this experiment. How has this absorption mechanism come about, without the obvious use of lures or other structures to attract insects? And how does teasel maximize upon its own morphology in the wild, if at all? What would the results be if these experiments were recreated on other similar species?

There are studies being conducted all the time that further the boundaries of what we know about these stationary organisms. There are new discoveries waiting just around the corner. Carnivory in plants is amazing because it transcends common notions about plants; especially in the case of the unassuming teasel.

Selected Resources:

- Wikipedia – Protocarnivorous Plant and Dipsacus fullonum

- USDA Forest Service: Dipsacus fullonum, Dipsacus laciniatus

- Darwin Online: Insectivorous Plants

———————

Jeremiah Sandler lives in southeast Michigan where he works in the plant health care industry. He has a degree in horticultural sciences and is an ISA certified arborist. He is interested in all things plant related and plans to own a horticulture business where he can share his passion with others. Follow Jeremiah on Instagram: @j.deepsea

———————

Would you like to write a guest post? Or contribute to Awkward Botany in some other way? Find out how.