“There is the great blank area where no red squirrels have returned, and this is where the grey ones first spread and are now permanent inhabitants. Outside it there are plenty of red squirrel populations still, though they have fluctuated, often severely.” — Charles Elton, The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants, 1958

Sciurus vulgaris, or the Eurasian red squirrel, is widespread throughout northern Europe and east into Siberia. It is a small squirrel with a chestnut top and a creamy underside that spends much of its time in the tops of trees. Its tail is large and fluffy, and its ears are adorned with prominent tufts of hair. It enjoys a broad range of foods from seeds, fruits, and leaves to fungi, insects, and birds’ eggs. It is beloved in the United Kingdom, where its survival is being threatened by a North American cousin. This cousin, now established in the U.K. for well over a century, looks to increase its range across Europe, with a growing population in Italy and the potential to spread to neighboring countries.

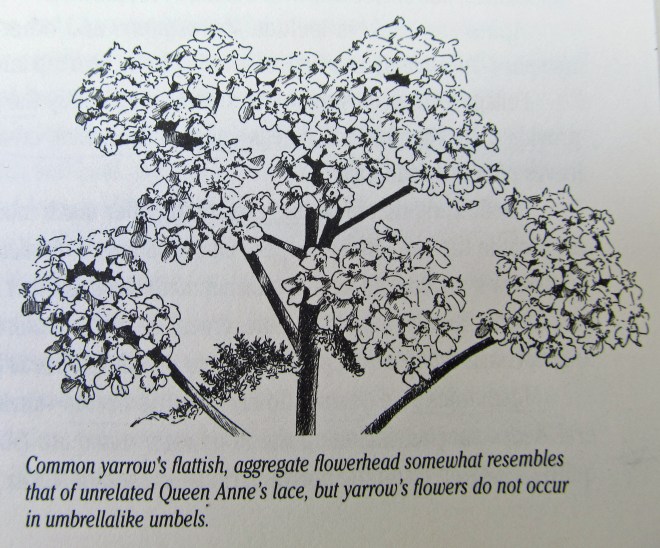

Eurasian red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) – photo credit: wikimedia commons

Sciurus carolinensis, or Eastern gray squirrel, is native to eastern North America but has been introduced to parts of western North America as well as other parts of the world, including the United Kingdom, Italy, South Africa, and Australia. Its fur is typically dark to pale gray with red tones. It prefers mature forests where food and shelter are abundant; however, it is a highly adaptable species and is common in urban areas and disturbed sites. It shares habitat requirements with the red squirrel, but has the advantages of being larger, stronger, and able to digest acorns.

Gray squirrels were first introduced to the U.K. in 1876. Wealthy collectors were enchanted by them and began releasing them on their estates. The first pair made it to Ireland in 1911. Around this time biologists were becoming concerned by how quickly they were spreading as well as the damage they were doing to young trees and the effect they seemed to be having on red squirrel populations. The U.K. Parliament responded in 1937 by banning the possession and introduction of gray squirrels. In an article published in Science in June 2016, Erik Stokstad writes about this “troubling phenomenon: where gray squirrels established colonies, red squirrels sooner or later vanished.” The current population of red squirrels in the U.K. is estimated at around 140,000, while gray squirrels are thought to number more than 2.5 million.

Why red squirrels vanish when grey squirrels are present is not entirely understood. Competition for food is one factor. Grey squirrels seem to have an advantage over red squirrels in mixed deciduous forests, and according to Schuchert, et al. (Biological Invasions, 2014), after colonization by gray squirrels, red squirrels can become restricted to coniferous forests, which are “less favored by grey squirrels.”

But direct competition alone doesn’t explain the plummeting numbers of reds in the presence of grays. Another explanation was identified in 1981 – grey squirrels were spreading a disease. Several years of experimentation confirmed that red squirrels were dying of squirrelpox – a parapoxvirus that gray squirrels carry but show little or no sign of infection. The virus can spread quickly through a population of red squirrels, leaving them lethargic, malnourished, and an easy target for predators. Stokstad writes, “red squirrels are defenseless…as [they] succumb, gray squirrels quickly take over the habitat.

But not all grey squirrels carry the virus, and there are some regions where the virus isn’t a major problem. Habitat loss and fragmentation due to human development also plays a role in the red squirrel’s decline. Add to that, grey squirrels may be more inclined to live among humans, giving them an advantage over the more reclusive reds.

Efforts have been underway for decades now to reduce, and even eliminate, gray squirrels in the U.K. Tens of thousands of grey squirrels have already been trapped and killed, yet they continue to dominate. Schuchert et al. write, “while culling may decrease grey squirrel population size in the short term, their high dispersal abilities makes re-colonization likely.” Funding for culling programs isn’t always available, and protests from animal rights groups like Animal Aide U.K. and Animal Ethics also have an impact. One area that culling has proved successful is Anglesey, an island off the coast of Wales, where the red squirrel population had once been reduced to just 40 individuals. Schuchert et al. analyzed culling data over a 13 year period and determined that trapping and killing efforts “resulted in the sustained and significant reduction of an established grey squirrel population at a regional landscape scale.”

Eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) – photo credit: wikimedia commons

Red squirrels may also be experiencing some relief thanks to another threatened mammal. Martes martes, or the European pine marten, is a member of the weasel family and, as Stokstad writes, “a cat-sized predator [that] was nearly exterminated in the 20th century.” Hunting, both for fur and pest control, and habitat loss reduced pine marten numbers dramatically until it received legal protection in 1988. Since then it has started to rebound, particularly in Scotland and Ireland. Anecdotes suggested that pine marten recovery in these areas was resulting in fewer gray squirrels. A study published in Biodiversity and Conservation in March 2014 confirmed that gray squirrel populations in Ireland were at “unusually low density,” and that the increasing numbers of pine martens played a role in that. Gray squirrels move slower and spend more time on the ground compared to red squirrels, making them easier prey for pine martens.

Efforts are now underway to introduce pine martens to other parts of the U.K. where gray squirrel populations are problematic. However, according to Stokstad, “red squirrel advocates worry that the pine marten could be a false hope, promising a free and uncontroversial solution that could threaten funds for culling.”

Let’s remember that the gray squirrel was deliberately introduced to the United Kingdom by humans, and that human activity is one of the main reasons for the grey squirrel’s explosion and the red squirrel’s retreat. Culling is not likely to ever eliminate gray squirrels completely, yet no one wants to see red squirrels go extinct. Altered landscapes can favor certain species over others, so ensuring that there is plenty of favorable habitat available for the red squirrel is one way to aid its survival. The grays may be there to stay, but let’s hope a compromise can be found so generations to come can benefit from sharing space with the red squirrel (and perhaps the gray squirrel,too).

Tufty Fluffytail, a character developed to help teach kids road safety in the U.K., saves Willy Weasel from getting run over (again).