This post originally appeared on Awkward Botany in November 2013. I’m reposting an updated version for the Year of Pollination series because it describes a very unique and incredibly interesting interaction between plant and pollinator.

Ficus is a genus of plants in the family Moraceae that consists of trees, shrubs, and vines. Plants in this genus are commonly referred to as figs, and there are nearly 850 described species of them. The majority of fig species are found in tropical regions, however several occur in temperate regions as well. The domesticated fig (Ficus carica), also known as common fig, is widely cultivated throughout the world for its fruit.

Common Fig (Ficus carica) – photo credit: wikimedia commons

The fruit of figs, also called a fig, is considered a multiple fruit because it is formed from a cluster of flowers. A small fruit develops from each flower in the cluster, but they all grow together to form what appears to be a single fruit. The story becomes bizarre when you consider the location of the fig flowers. They are contained inside a structure called a syconium, which is essentially a modified fleshy stem. The syconium looks like an immature fig. Because they are completely enclosed inside syconia, the flowers are not visible from the outside, yet they must be pollinated in order to produce seeds and mature fruits.

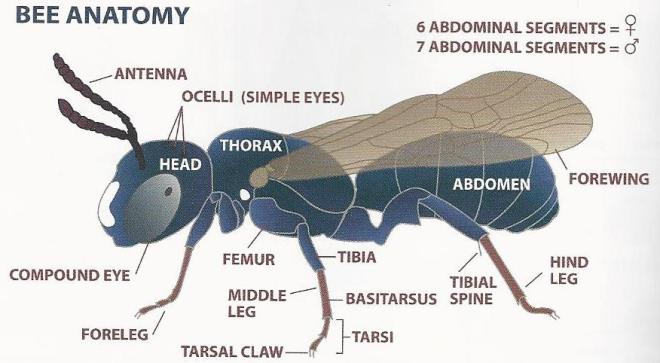

This is where the fig wasps come in. “Fig wasp” is a term that refers to all species of chalcid wasps that breed exclusively inside of figs. Fig wasps are in the order Hymenoptera (superfamily Chalcidoidea) and represent at least five families of insects. Figs and fig wasps have coevolved over tens of millions of years, meaning that each species of fig could potentially have a specific species of fig wasp with which it has developed a mutualistic relationship. However, pollinator host sharing and host switching occurs frequently.

Fig wasps are tiny, mere millimeters in length, so they are not the same sort of wasps that you’ll find buzzing around you during your summer picnic. Fig wasps have to be small though, because in order to pollinate fig flowers they must find their way into a fig. Fortunately, there is a small opening at the base of the fig called an ostiole that has been adapted just for them.

What follows is a very basic description of the interaction between fig and fig wasp; due to the incredible diversity of figs and fig wasps, the specifics of the interactions are equally diverse.

First, a female wasp carrying the pollen of a fig from which she has recently emerged discovers a syconium that is ready to be pollinated. She finds the ostiole and begins to enter. She is tiny, but so is the opening, and so her wings, antennae, and/or legs can be ripped off in the process. No worries though, since she won’t be needing them anymore. Inside the syconium, she begins to lay her eggs inside the flowers. In doing so, the pollen she is carrying is rubbed off onto the stigmas of the flowers. After all her eggs are laid, the female wasp dies. The fig wasp larvae develop inside galls in the ovaries of the fig flowers, and they emerge from the galls once they have matured into adults. The adult males mate with the females and then begin the arduous task of chewing through the wall of the fig in order to let the females out. After completing this task, they die. The females then leave the figs, bringing pollen with them, and search for a fig of their own to enter and lay eggs. And the cycle continues.

But there is so much more to the story. For example, there are non-pollinating fig wasps that breed inside of figs but do not assist in pollination – freeloaders essentially. The story also differs if the species is monoecious (male and female flowers on the same plant) compared to dioecious (male and female flowers on different plants). It’s too much to cover here, but figweb.org is a great resource for fig and fig wasp information. Also check out the PBS documentary, The Queen of Trees.