Boise, Idaho is frequently referred to as the City of Trees despite being located in a semiarid region of the Intermountain West known as the sagebrush steppe where few trees naturally grow. It earns this moniker partly because the name Boise is derived from the river that runs through it (the Boise River), which was named La Rivere Boisse, or The Wooded River, by early French trappers. Although it flows through a largely treeless landscape, The Wooded River was an apt name on account of the wide expanse of cottonwoods and willows that grew along its banks. The fervent efforts of early colonizers to plant trees in large numbers across their new city also helped Boise earn the title, City of Trees. Today, residents continue the legacy of planting trees, ensuring that the city will remain wooded for decades to come.

As is likely the case for most urban areas, the majority of trees being planted in Boise are not native to the region. After all, very few tree species are. However, apart from the trees that flank the Boise River, there is one tree in particular that naturally occurs in the area. Celtis reticulata, commonly known as netleaf hackberry, can be found scattered across the Boise Foothills amongst shrubs, bunchgrasses, and wildflowers, taking advantage of deep pockets of moisture found in rocky outcrops and draws.

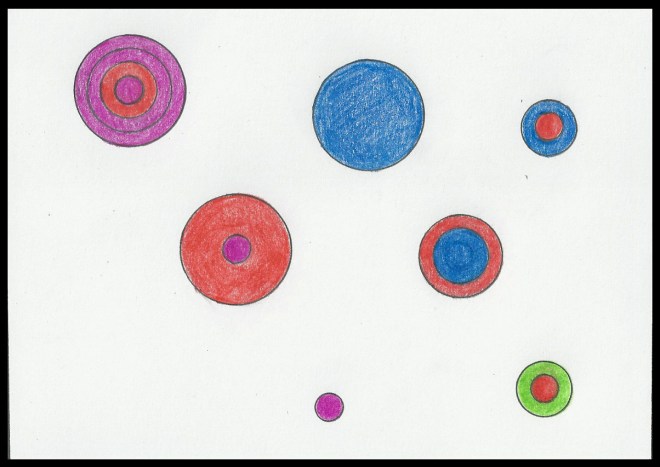

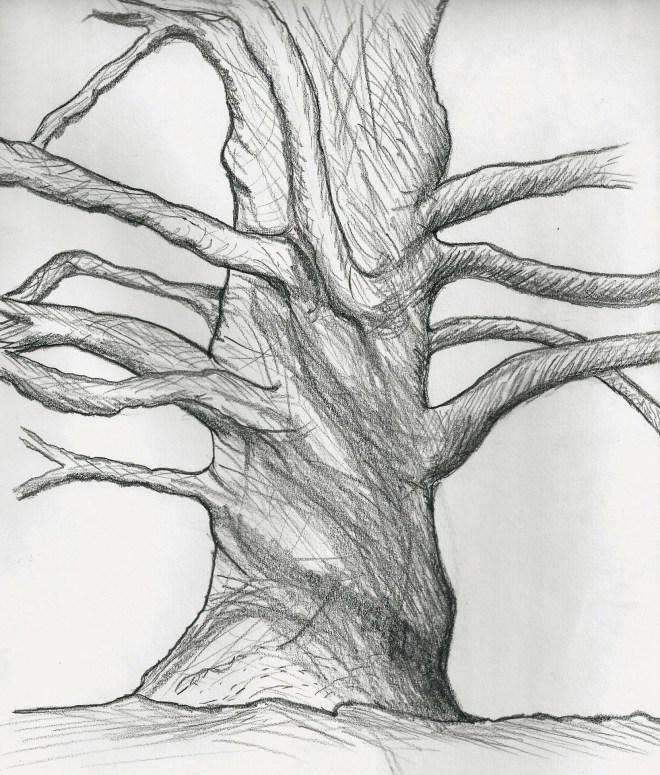

The western edge of netleaf hackberry’s range extends to the northwest of Boise into Washington, west into Oregon, and down into California. The majority of its range is found south of Idaho, across the Southwest and into northern Mexico, then east into the prairie regions of Kansas and Oklahoma. Previously placed in the elm family, it is now considered a member of the family Cannabaceae (along with hemp and hops). It’s a relatively small, broad tree (sometimes a shrub) with a semi-rounded crown. It grows slowly, is long-lived, and generally has a gnarled, hardened, twisted look to it. It’s a tough tree that has clearly been through a lot.

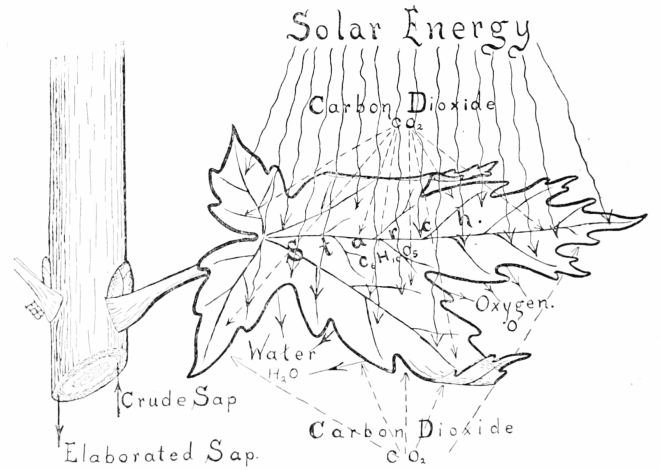

The leaves of Celtis reticulata are rough, leathery, and oval to lance shaped with serrate or entire leaf margins. Their undersides have a distinct net-like pattern that gives the tree its common name. A very small insect called a hackberry psyllid lays its eggs inside the leaf buds of netleaf hackberries in the spring. Its larvae develop inside the leaf, feeding on the sugars produced during photosynthesis, and causing nipple galls to form in the leaves. It’s not uncommon to see a netleaf hackberry with warty-looking galls on just about every leaf. Luckily, the tree doesn’t seem to be bothered by this.

The fruit of netleaf hackberry is a pea-sized drupe that hangs at the end of a pedicel that is 1/4 to 1/2 inch long. Its skin is red-orange to purple-brown, and its flesh is thin with a large seed in the center. The fruits, along with a few random leaves, persist on the tree throughout the winter and provide food for dozens of species of birds and a variety of mammals.

Celtis reticulata is alternately branched. Its twigs are slender, zig-zagging, and often curved back towards the trunk. They are reddish-brown with several pale lenticels and have sparse, fine, short hairs that are hard to see without a hand lens. The leaf scars are small, half-round, and raised up from the twig. They have three bundle scars that form a triangle. The buds are triangle-shaped with fuzzy bud scales that are slightly lighter in color than the twig. The twigs are topped with a subterminal bud, and the pith (the inner portion of the twig) is either chambered or diaphragmed and difficult to see clearly without a hand lens.

The young bark of netleaf hackberry is generally smooth and grey, developing shallow, orange-tinged furrows as it gets older. Mature bark is warty like its cousin, Celtis occidentals, and develops thick, grey, corky ridges. Due to its slow growth, the bark can be retained long enough that it becomes habitat for extensive lichen colonies.

Netleaf hackberry is one of the last trees to leaf out in the spring, presumably preserving as much moisture as possible as it prepares to enter another scorching hot, bone-dry summer typical of the western states. Its flowers open around the same time and are miniscule and without petals. Their oversized mustache-shaped, fuzzy, white stigmas provide some entertainment for those of us who take the time to lean in for a closer look.

More Winter Trees and Shrubs on Awkward Botany:

———————

Photos of netleaf hackberry taken at Idaho Botanical Garden in Boise, Idaho.