“If it wasn’t for the plants, and if it wasn’t for the invertebrates, our ancestors’ invasion of land could never have happened. There would have been no food on land. There would have been no ecosystems for them to populate. So really the whole ecosystem that Tiktaalik and its cousins were moving into back in the Devonian was a new ecosystem. … This didn’t exist a hundred million years before – shallow fresh water streams with soils that are stabilized by roots. Why? Because it took plants to do that – to make the [habitats] in the first place. So really plants, and the invertebrates that followed them, made the habitats that allowed our distant relatives to make the transition from life on water to life on land.” – Neil Shubin, author of Your Inner Fish, in an interview with Cara Santa Maria on episode 107 of her podcast, Talk Nerdy To Me

Plants were not the first living beings to colonize land – microorganisms have been terrestrial for what could be as long as 3.5 billion years, and lichens first formed on rocks somewhere between 550 and 635 million years ago – however, following in the footsteps of these other organisms, land plants paved the way for all other forms of terrestrial life as they migrated out of the waters and onto dry land.

The botanical invasion of land was a few billion years in the making and is worth a post of its own. What’s important to note at this point, is that the world was a much different place back then. For one, there was very little free oxygen. Today’s atmosphere is 21% oxygen; the first land plants emerged around 470 million years ago to an atmosphere that was composed of a mere 4% oxygen. Comparatively, the atmosphere back then was very carbon rich. Early plants radiated into numerous forms and spread across the land and, through processes like photosynthesis and carbon sequestration, helped to dramatically increase oxygen levels. A recent study found that early bryophytes played a major role in this process. The authors of this study state, “the progressive oxygenation of the Earth’s atmosphere was pivotal to the evolution of life.”

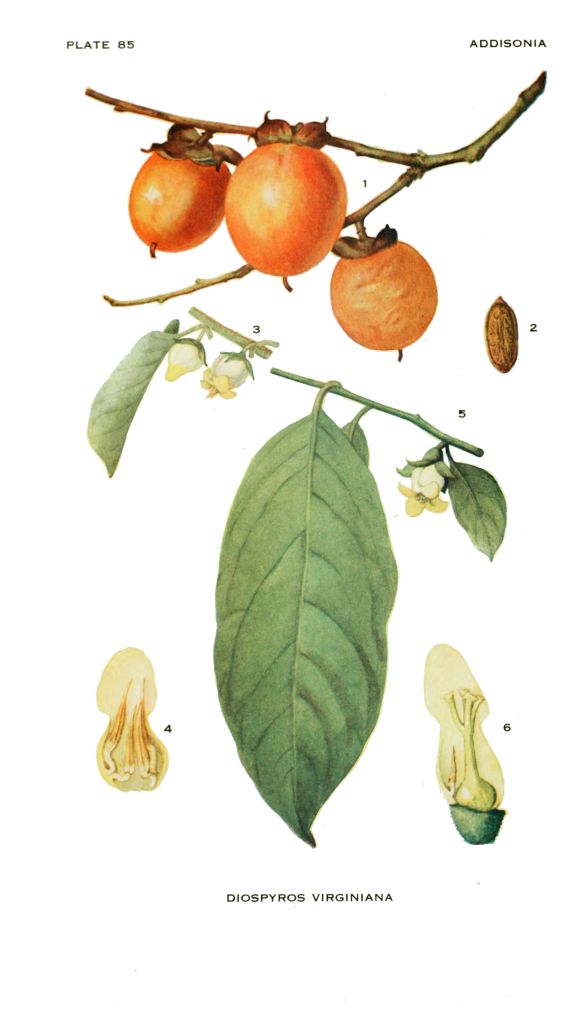

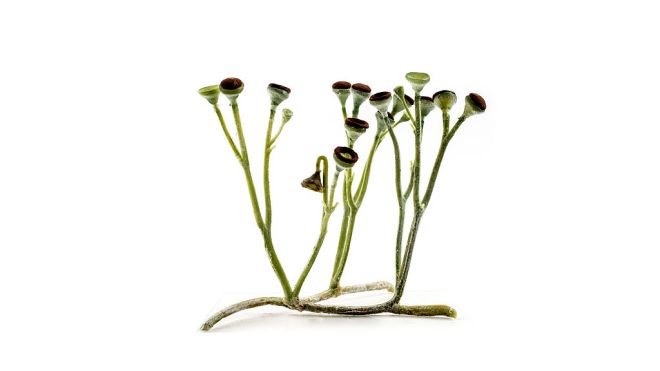

A recreation of a Cooksonia species – one of many early land plants (photo credit: wikimedia commons)

The first land plants looked very different compared to the plants we are used to seeing today. Over the next few hundred million years plants developed new features as they adapted to life on land and to ever-changing conditions. Roots provided stability and access to water and nutrients. Vascular tissues helped transport water and nutrients to various plant parts. Woody stems helped plants reach new heights. Seeds offered an alternative means of preserving and disseminating progeny. Flowers – by partnering with animal life – provided a means of producing seeds without having to rely on wind, water, or gravity. And that’s just scratching the surface. Rooted in place and barely moving, if at all, plants appear inanimate and inactive, but it turns out they have a lot going on.

But what is a plant again? In part one and two, we listed three major features all plants have in common – multicellularity, cell walls composed of cellulose, and the ability to photosynthesize – and we discussed how being an autotroph (self-feeder/producer) sets plants apart from heterotrophs (consumers). Joseph Armstrong writes in his book, How the Earth Turned Green, “photosynthetic producers occupy the bottom rung of communities.” In other words, “all modern ecosystems rely upon autotrophic producers to capture energy and form the first step of a food chain because heterotrophs require pre-made organic molecules for energy and raw materials.”

So, why should we care about plants? Because if it wasn’t for them, there wouldn’t be much life on this planet to speak of, including ourselves.

Plants don’t just provide food though. They provide habitat as well. Plus they play major roles in the cycling of many different “nutrients,” including nitrogen, phosphorous, carbon, sulfur, etc. They are also a major feature in the water cycle. It is nearly impossible to list the countless, specific ways in which plants help support life on this planet, and so I offer two examples: moss and dead trees.

The diminutive stature of mosses may give one the impression that they are inconsequential and of little use. Not so. In her book, Gathering Moss, Robin Wall Kimmerer describes how mosses support diverse life forms:

There is a positive feedback loop created between mosses and humidity. The more mosses there are, the greater the humidity. More humidity leads inexorably to more mosses. The continual exhalation of mosses gives the temperate rain forest much of its essential character, from bird song to banana slugs. … Without mosses, there would be fewer insects and stepwise up the food chain, a deficit of thrushes.

Mosses are home to numerous invertebrate species. For many insects, mosses are a place to deposit their eggs and, consequentially, a place for their larvae to mature into adults. Banana slugs traverse the moss feeding on “the many inhabitants of a moss turf, and on the moss itself.” In the process they help to disperse the moss.

Moss is used as a nesting material by various species of birds, as well as squirrels, chipmunks, voles, bears, and other animals. Patches of moss can also function as “nurseries for infant trees.” In some instances, mosses inhibit seed germination, but they can also help protect seeds from drying out or being eaten. Kimmerer writes, “a seed falling on a bed of moss finds itself safely nestled among leafy shoots which can hold water longer than the bare soil and give it a head start on life.”

Virtually all plants, from the tiniest tufts of grass to the tallest, towering trees have similar stories to tell about their interactions with other living things. Some have many more interactions than others, but all are “used” in some way. And even after they die, plants continue to interact with other organisms, as is the case with standing dead trees (a.k.a. snags).

In his book, Welcome to Subirdia, John Marzluff explains that when “hole creators” use dead and dying trees, they benefit a host of “hole users:”

Woodpeckers are natural engineers whose abandoned nest and roost cavities facilitate a great diversity of life, including birds, mammals, invertebrates, and many fungi, moss, and lichens. Without woodpeckers, birds such as chickadees and tits, swallows and martins, bluebirds, some flycatchers, nuthatches, wood ducks, hooded mergansers, and small owls would be homeless.

As plants die, they continue to provide food and habitat to a variety of other organisms. Eventually they are broken down to their most rudimentary components, and their nutrients are taken up and used by “new life.” Marzluff elaborates on this process:

Much of the ecological web exists out of sight – underground and in rotting wood. There, molds, bacteria, fungi, and a world of invertebrates convert the last molecules of sun-derived plant sugar to new life. These organisms are technically ‘decomposers,’ but functionally they are among the greatest of creators. Their bodies and chemical waste products provide us with an essential ecological service: soil, the foundation of terrestrial life.

Around 470 million years ago, plants found their way to land. Since then life of all kinds have made land their home. Plants helped lead the way. Today, plants continue their long tradition of supporting the living, both in life and in death.