When garden plants go weedy, it doesn’t necessarily mean they’ve escaped the boundaries of our yards and invaded nearby natural areas or uncultivated spaces. While this is a concern for a significant number of ornamental plants, sometimes the weediness of a garden plant is experienced within the very yard or garden it was planted in. For some of us, such a plant’s weediness can turn us off from growing it at all. We opt to weed out the overzealous plants and replace them with something tamer. Others may decide to just put up with this behavior. Perhaps we like the plant too much to get rid of it, so we simply accept its overly competitive nature. We may even welcome its ability to take any and all available ground. Why toil away trying to get something else to grow, when our weedy friends take up space with little to no effort on our part?

This seems to be the story of violets. While certainly not all violets exhibit this behavior – some species are actually downright difficult to grow – there are a select number of species that are proficient at propagating themselves and spread readily. They capitalize quickly on open ground and set up shop before anything else has the chance. Given the opportunity, they may even snuff out other plants and take their place. I’ve dealt with the latter myself, as violets moved in on some mat-forming penstemons and eventually took them out.

While violets can and will act aggressively in garden beds, ire towards their unruly behavior seems to stem largely from their activity in lawns. There is an expectation that lawns be grass species only, and any other plant that finds its way in gets labeled as an intruder that must be stopped. While some people tolerate (and even encourage) a few guests – which I think is a reasonable approach – others prefer grass and grass alone. Whatever your preference is, violets can become too much. Grass often has a difficult time competing with the broad, evergreen leaves of violets and their horizontally spreading rhizomes and stolons. As violet colonies expand, the grass succumbs, and broad patches of violets can become dominant in declining lawns.

At least three species of violets are particularly notorious for invading lawns in North America: Viola odorata, Viola sororia, and Viola riviniana. Sweet violet, or V. odorata, is a perennial plant from Eurasia that forms dense mats with the help of rhizomes and leafy stolons. Its leaves are oval to heart-shaped with toothed margins. Solitary flowers rise above the foliage on slender, hooked stalks. Flowers are white to various shades of purple and have a sweet scent. Common blue violet, or V. sororia, is native to North America and looks very similar to sweet violet. The two species can also hybridize. Common blue violet tends to have more heart-shaped leaves and broader flowers. It also produces only rhizomes, no stolons.

Dog violet or wood violet (V. riviniana) is another similar-looking plant from Eurasia that – depending on what source you reference – either does or does not spread by stolons. This confusion could arise if sprawling stems are rooting at the nodes and being mistaken for stolons, which almost seems like a distinction without a difference. If you’ve seen this plant in a garden setting, there is a good chance it is the commercially popular, purple-leaved form (V. riviniana Purpurea Group).

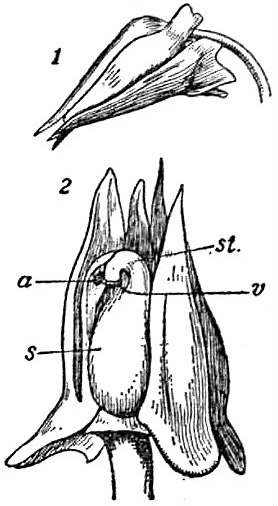

All of these violets flower in the spring, and sometimes resume flowering in the fall. Their fruits are capsules, which upon ripening split open and fling out several tiny, shiny seeds. There ability to spread readily both by seed and vegetatively is a reason they are so successful at getting around. And if that weren’t enough, they have a secret weapon called cleistogamous flowers. These are flowers that never open for cross-pollination. Instead, they remain closed and opt for self pollination. Their fruits ripen, split open, and release seeds, often coming equipped with elaiosomes – a little packet of food that encourages seed dispersal by ants. These cleistogamous flowers appear in late summer/early fall and are hidden below the foliage either at or below the soil. With so many options for reproduction and dispersal, its easy to see why lawn violets can frustrate many gardeners.

Lawn invaders invade lawns because they are adapted to the conditions found there. Lawns are often well-watered, so the soil stays moist. The soil is also generally compacted due to regular foot traffic, etc. Plants with low growing foliage escape the blades of mowers, which would kill or set back other weeds with more upright foliage and stems. These are all reasons why violets take well to turfgrass. They tend to prefer shady, cool, moist locations, but can also tolerate full sun and dry soils. Once they have gained footing in a shady part of the lawn, their superb ability to reproduce and spread allows them to expand their territory, particularly in lawns that are poorly maintained. Luckily, their roots are shallow and the plants are easy enough to dig up and remove. If you are tenacious enough, they can be largely eliminated. Or, just learn to accept their presence and appreciate them for their carpet of attractive flowers in the spring and their broad, evergreen leaves year-round. It could be worse.