Hellstrip Gardening by Evelyn J. Hadden is a book intended to help transform roadside beds (or any neglected or hard to garden spot) into a verdant and productive green space. A “paradise,” if you will. Last week, I introduced the concept of hellstrips and briefly discussed the first section of Hadden’s book. This week we are looking at the second section, which is all about the unique challenges and obstacles that hellstrip gardening entails. Hadden has divided this section into 8 main areas of focus. She provides a ton of great information that is sure to be incredibly useful for anyone seriously engaged in improving a hellstrip. If you are one of those people, I highly recommend referring to the book. For simplicity’s sake, this post will include a quick overview of each of the main themes, detailing a few of the things that stood out to me.

Working with Trees

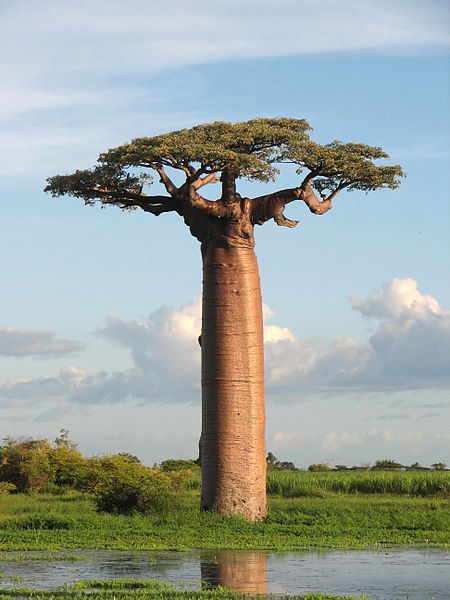

Trees offer many benefits to urban and suburban areas; however, it is not uncommon to see hellstrips with trees that are much too large for the space. Hellstrips are often surrounded by paved surfaces and are heavily trafficked. This leads to soil compaction which results in roots being starved of oxygen and water. Where there are power lines overhead, oversized trees must be heavily pruned to make room for them. Consider planting small or medium sized trees in these spaces. Make sure the soil is well aerated and that there is enough space for the roots to expand out beyond the canopy. Hadden advises avoiding growing turfgrass below trees because it is shallow rooted and uses up much of the available water and oxygen; instead plant deep rooted perennials that naturally grow in wooded environments.

Working with Water

Depending on where you are located, your hellstrip is either going to be water limited or water abundant. Water availability also varies depending on the time of year. If you are mostly water limited, include plants that can tolerate drought conditions. Avoid planting them too close to each other so that they aren’t competing for water. Increase your soil’s water holding capacity by adding organic matter and mulching bare ground. Strategically placed boulders can create cool, moist microclimates where plants can endure hot, dry stretches. If you are dealing with too much water, you can “increase the absorption power” of your property by ensuring that your soil is well aerated and high in organic matter. Plant high water use perennials, grasses, shrubs, and trees with extensive root systems. Replace impermeable surfaces with ground covers and permeable pathways to reduce runoff, and reshape beds so that they collect, hold, and absorb excess runoff.

Working with Poor Soil

Curbside beds in urban areas are notorious for having soil that is compacted, contaminated, and depleted of nutrients. This issue can be addressed by removing and replacing the soil altogether or by heavily amending it. Another solution is to only include plants that can tolerate these harsh conditions. Most likely you will do something in between these two extremes. Adding organic matter seems like the best way to improve soil structure and fertility. Because contaminants from paved surfaces are regularly introduced to curbside gardens, there is a good chance that the soil may contain high levels of lead and other heavy metals. It is a good idea to test the soil before planting edibles. Contaminated soils can be remediated by growing certain plants like annual sunflowers, which take up heavy metals into their tissues. These plants must then be disposed of as hazardous waste.

Common sunflower (Helianthus annuus) is one of several plants that can be used to remediate polluted soil (photo credit: www.eol.org)

Working with Laws and Covenants

Regulations and restrictions may prohibit you from creating the hellstrip garden you dream of having. Start by informing yourself of your areas laws and covenants. Some restrictions may be based on public safety (such as restrictions on street trees) while others may be based on outdated ways of thinking. Hadden advises not to assume that a regulation can’t be reversed; however, first you must prepare a well reasoned argument based on facts and evidence. Will your landscape design conserve resources, provide ecological services, improve property values, enhance the neighborhood in some way? Perhaps “your property can model a new landscaping strategy.” Prepare to state your case respectfully, intelligently, and convincingly, and you might just find yourself at the forefront of a new movement.

Living with Vehicles

A garden growing along a roadway is sure to be confronted by vehicles. Hadden suggests using “easily replaceable plants for vulnerable areas.” You can also protect your garden by installing a low fence or wall or by planting sturdy shrubs, prickly plants, or plants that are tall and/or brightly colored. If parking is a regular occurrence, leave room for people to exit their vehicles without trampling the garden. A garden surrounded by paved surfaces will be hotter than other areas on your property, so plant heat tolerant plants or shade the garden with trees and shrubs. A hedge, trellis, fence, or berm can act as a wind and dust break and can help reduce noise. Aromatic plants can help combat undesirable urban smells, and noise can be further masked by water features and plantings that attract songbirds.

Living with Wildlife

Wildlife can either be encouraged or discouraged depending on your preferences. Discouraging certain wildlife can be as simple as “learn[ing] what they need in terms of food and shelter, and then eliminat[ing] it.” A garden full of diverse plant life can help limit damage caused by leaf-eating insects. Encouraging birds and bats can also help control insects. Herbivory by mammals can be reduced by growing a wide array of plants and not over fertilizing or overwatering them. Conversely, encouraging wildlife entails discovering what they like and providing it. For example, to encourage large populations of pollinators, plant a diversity of plants that flower throughout the year and provide nesting sites such as patches of bare ground for ground nesting bees. Keep in mind that your property can be part of a wildlife corridor – a haven for migrating wildlife in an otherwise sea of uninhabitable urban space.

Living with Road Maintenance and Utilities

Curbsides gardens are unique in that they are directly affected by road maintenance and they often must accommodate public utility features like electrical boxes, fire hydrants, street signs, and telephone poles. In areas where salts are applied to roads to reduce ice, hellstrips can be planted with salt tolerant plants and can be deeply watered in order to flush salts down into the soil profile. In areas that receive heavy snowfall, avoid piling snow directly on top of plants. Always call utility companies before doing any major digging to find out where underground pipes and electrical cables are located. Utility features can be masked using shrubs, trellises, and vining plants (especially annual vines that are easily removed and replaced); just be sure to maintain access to them. If your hellstrip consists of “unsightly objects,” Hadden recommends “composing a riveting garden scene to divert attention from an uninspiring view.”

Living with the Public

Your hellstrip is the most public part of your yard, so you are going to have to learn to share. In order to keep trampling to a minimum and contained to certain areas, make it obvious where pathways are and use berms to raise up the beds. Keep the paths clear of debris and avoid messy fruit and nut trees that can make pathways unfriendly to walk on. Avoid planting rare and valuable plants in your curbside garden. Remember that your hellstrip is typically the first part of your property that people see, so make a good first impression. Also, consider the potential that your public hellstrip garden has for building community and inspiring others.

There is so much more in this section; it is impossible to discuss it all here. Again, if you are serious about improving a hellstrip, get your hands on this book. All hellstrips are different and will have unique challenges. Hadden does a great job of touching on nearly any issue that may arise. Now that we’ve covered challenges and obstacles, next week we will look at designing, building, and managing hellstrip gardens.