Have you ever tried to identify a grass? Most of us who like to look at plants and learn their names will probably admit that we often give up on grasses pretty quickly, or just ignore them entirely. They aren’t the easiest plants to identify to species, and there are so many of them. Without close inspection, they can all look pretty similar. Their flowers aren’t particularly showy, and their fruits are fairly forgettable. They are strands or clumps of green that create a backdrop for more intriguing forms of vegetation. Yet, they are among the most ecologically and economically important groups of plants on the planet. And actually, if you can ascend the hurdles that come with getting to know them, they are beautiful organisms and really quite amazing.

The grass family – Poaceae – consists of nearly 8oo genera and about 12,000 species. Grasses occur in a wide range of habitats across the globe. Wherever you are on land, a grass is likely nearby. Grasses play vital roles in their ecosystems and, from a human perspective, are critical to life as we know it. We grow them for food, use them for building materials and fuel, plant them as ornamentals, and rely on them for erosion control, storm water management, and other ecosystem services. We may not acknowledge their presence most of the time, but we very likely wouldn’t be here without them.

The sheer number of grass species is one thing that makes them so difficult to identify. Key identifying features of grasses and grass-like plants (also known as graminoids) tend to be very small and highly modified compared to similar features on other flowering plants. This requires using a hand lens and learning a whole new vocabulary in order to begin to understand a grass’s anatomy. It’s a time commitment that goes beyond a lot of other basic plant identification, and it’s a learning curve that few dare to follow. However, once you learn the basic features, it becomes clear that grasses are relatively simple organisms, and once you start identifying them, it can actually be an exciting and rewarding experience.

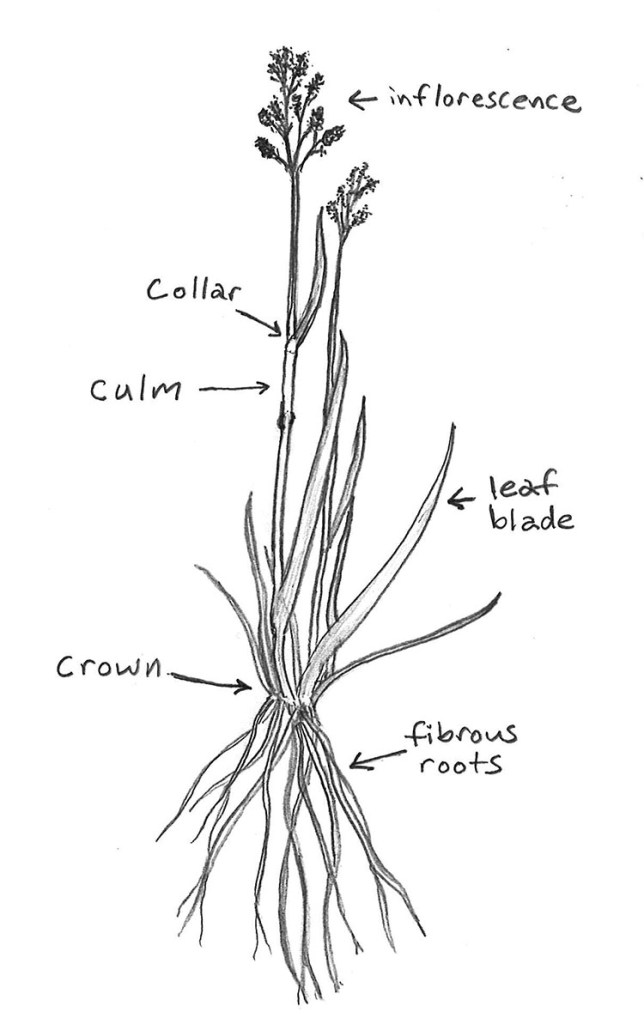

Depending on the species, grasses can be annuals – completing their life cycle within a single year – or perennials – coming back year after year for two or more years. Most grasses have a fibrous root system; some are quite shallow and simple while others are extremely deep and extensive. Some species of perennial grasses spread by either rhizomes (underground stems), stolons (horizontal, above ground stems), or both. Some grasses also produce tillers, which are essentially daughter plants that form at the base of the plant. The area where roots, rhizomes, stolons, and tillers meet the shoots and leaves of a grass plant is called the crown. This is an important region of the plant, because it allows for regrowth even after the plant has been browsed by a grazing animal or mown down by a lawn mower.

The stem or shoot of a grass is called a culm. Leaves are formed along the lengths of culms, and culms terminate in inflorescences. Leaves originate at swollen sections of the culm called nodes. They start by wrapping around the culm and forming what is called a leaf sheath. Leaves of grasses are generally long and narrow with parallel venation – a trait typical of monocotyledons. The part of the leaf that extends away from the culm is called the leaf blade or lamina. Leaves are alternatively arranged along the length of the stem and are two-ranked, meaning they form two distinct rows opposite of each other along the stem.

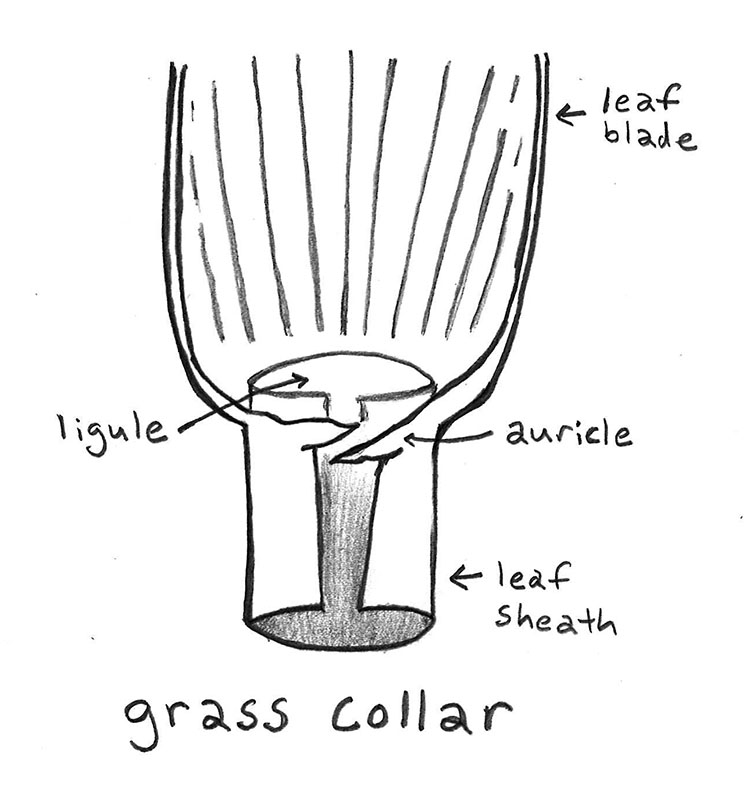

The area where the leaf blade meets the leaf sheath on the culm is called the collar. This collar region is important for identifying grasses. With the help of a hand lens, a closer look reveals the way in which the leaf wraps around the culm (is it open or closed?), whether or not there are hairs present and what they are like, if there are auricles (small flaps of leaf tissue at the top of the collar), and what the ligule is like. The ligule is a thin membrane (sometimes a row of hairs) that forms around the culm where the leaf blade and leaf sheath intersect. The size of the ligule and what its margin is like can be very helpful in identifying grasses.

The last leaf on the culm before the inflorescence is called the flag leaf, and the section of the culm between the flag leaf and the inflorescence is called a peduncle. Like the collar, the flower head of a grass is where you’ll find some of the most important features for identification. Grass flowers are tiny and arranged in small groupings called spikelets. In general, several dozen or hundreds of spikelets make up an inflorescence. They can be non-branching and grouped tightly together at the top of the culm, an inflorescence referred to as a spike, or they can extend from the tip of the culm (or rachis) on small branches called pedicels, an inflorescence referred to as a raceme. They can also be multi-branched, which is the most common form of grass inflorescence and is called a panicle.

Either way, you will want to take an even closer look at the individual spikelets. Two small bracts, called glumes, form the base of the spikelet. Above the glumes are a series of florets, which are enclosed in even smaller bracts – the outer bract being the lemma and the inner bract being the palea. Certain features of the glumes, lemmas, and paleas are specific to a species of grass. This includes the way they are shaped, the presence of hairs, their venation, whether or not awns are present and what the awns are like, etc. If the grass species is cleistogamous – like cheatgrass – and the florets never open, you will not get a look at the grass’s sex parts. However, a close inspection of an open floret is always a delight. A group of stamens protrude from their surrounding bracts bearing pollen, while feathery stigmas reach out to collect the pollen that is carried on the wind. Depending on the species, an individual grass floret can have either only stamens, only pistils (the stigma bearing organs), or both. Fertilized florets form fruits. The fruit of a grass is called a caryopsis (with a few exceptions) and is indistinguishable from the seed. This is because the seed coat is fused to the wall of the ovary, unlike other fruit types in which the two are separate and distinct.

If all this doesn’t make you want to run outside and take a close look at some grasses, I don’t know what will. What grasses can you identify in your part of the world? Let me know in the comment section below or check out the linktree and get in touch by the means that suits you best.