First off, let’s get one thing straight – tomatoes are fruits. Now that that is settled, guess what is also a fruit? This:

(photo credit: wikimedia commons)

Yep. It’s a dandelion fluff. More accurately, it is a dandelion fruit with a pappus attached to it. Botanically speaking, a fruit is the seed-bearing, ripened ovary of a flowering plant. Other parts of the plant may be incorporated into the fruit, but the important distinction between fruits and other parts of a plant is that a seed or seeds are present. In fact, the purpose of fruits is to protect and distribute seeds. Which explains why tomatoes are fruits, right? (And, for that matter, the dandelion fluff as well.) So why the tired argument over whether or not a tomato is a fruit or a vegetable? This article may help explain that.

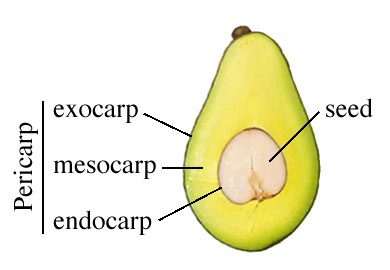

Before going into types of fruits, it may be important to understand some basic fruit anatomy. Pericarp is a term used to describe the tissues of a fruit surrounding the seed(s). It mainly refers to the wall of a ripened ovary, but it has also been used in reference to fruit tissues that are derived from other parts of the flower. Pericarps consist of three layers (although not all fruits have all layers): endocarp, mesocarp, and exocarp (also known as epicarp). The pericarps of true fruits consist of only ovarian tissue, while the pericarps of accessory fruits consist of other flower parts such as sepals, petals, receptacles, etc.

(photo credit: University of California ANR)

Fruits can be either fleshy or dry. Tomatoes are fleshy fruits, and dandelion fluffs are dry fruits. Dry fruits can be further broken down into dehiscent fruits and indehiscent fruits. Dehiscent fruits – like milkweeds and poppies – break open as they reach maturity, releasing the seeds. Indehiscent fruits – like sunflowers and maples – remain closed at maturity, and seeds remain contained until the outer tissues rot or are removed by some other agent.

Most fruits are simple fruits, fruits formed from a single ovary or fused ovaries. Compound fruits are formed in one of two ways. Separate carpels in a single flower can fuse to form a fruit, which is called an aggregate fruit; or all fruits in an inflorescence can fuse to form a single fruit, which is called a multiple fruit. A raspberry is an example of an aggregate fruit, and a pineapple is an example of a multiple fruit.

Additional terms used to describe fruit types:

Berry – A familiar term, berries are fleshy fruits with soft pericarp layers. Grapes, tomatoes, blueberries, and cranberries are examples of berries.

Pome – Pomes are similar to berries but have a leathery endocarp. Apples, pears, and quinces are examples of pomes. When you are eating an apple and you reach the “core,” you have reached the endocarp. Most – if not all – pomes are accessory fruits because they consist of parts of flowers in addition to the ovarian wall, such as – in the case of apples and pears – the receptacle.

Drupe – Drupes are also similar to berries but have hardened endocarps. Peaches, plums, cherries, and apricots are examples of drupes. A “pit” consists of a hardened endocarp and its enclosed seed.

Pepo – Pepos are also berry-like but have tough exocarps referred to as rinds. Pumpkins, melons, and cucumbers are examples of pepos.

Hesperidium – Another berry-like fruit but with a leathery exocarp. Oranges, lemons, and tangerines are examples of this type of fruit.

Caryopsis – An indehiscent fruit in which the seed coat fuses with the fruit wall and becomes nearly indistinguishable. Corn, oats, and wheat are examples of this type of fruit.

Achene – An indehiscent fruit in which the seed and the fruit wall do not fuse and remain distinguishable. Sunflowers and dandelions are examples of achenes.

Samara – An achene with wings attached. Maples, elms, and ashes all produce samaras. Remember as a kid finding maple fruits on the ground, throwing them into the air, and calling them “helicopters.” Those were samaras.

The fruits of red maple, Acer rubrum (photo credit: eol.org)

Nut – An indehiscent fruit in which the pericarp becomes hard at maturity. Hazelnuts, chestnuts, and acorns are examples of nuts.

Follicle – Dehiscent fruits that break apart on a single side. Milkweeds, peonies, and columbines are examples of follicles.

Legume – Dehiscent fruits that break apart on multiple sides. Beans and peas are examples of legumes.

Capsule – This term describes a number of dehiscent fruits. It differs from follicle and legume in that it is derived from multiple carpels. Capsules open in several ways, including along lines of fusion, between lines of fusion, into top and bottom halves, etc. The fruits of iris, poppy, and primrose are examples of capsules.

Flowers and fruits are key to identifying plants. Learning to recognize these structures will help you immensely when you want to know what you are looking at. And now that it is harvest season, you can impress your friends by calling fruits by their proper names. Pepo pie, anyone?