While we’re on the subject of pollen-gluing mechanisms, there is another material apart from pollenkitt that a limited number of flowering plant families use to link their pollen grains together. It functions, much like pollenkitt, by aiding in the attachment of pollen to visiting animals. However, unlike pollenkitt, it isn’t sticky, oily, or viscous, and is instead more like a series of threads. Viscin threads to be exact.

One of the major differences between pollenkitt and viscin threads is their composition. The lipid-rich coating that surrounds pollen grains, which we call pollenkitt, is derived from breakdown materials of an inner layer of the anther. It is added to pollen grains after they are formed and before the anther dehisces. Viscin threads are made up of sporopollenin, the same biopolymer that exine (the outer wall of a pollen grain) is composed of. Viscin threads have points of attachment on an outer layer of the exine called the ektexine. Unlike pollenkitt, viscin threads don’t add new color to pollen grains, nor do they contain scent compounds. Their thickness, length, abundance, and texture are dependent on the species of plant they are found on, much like pollenkitt varies in form and composition depending on species.

Viscin threads evolved independently in three distantly related plant families. These include Onagraceae (the evening primrose family), Ericaceae (the heath family), and a subfamily in the pea family known as Caesalpinioideae (the peacock flower subfamily). Viscin threads are found in many, but not all, of the species in these three families. Some species in other plant families have what appear to be viscin threads but are actually ropy strands of pollenkitt, as they are composed of pollenkitt and not sporopollenin. Because they are made up of the same durable material as exine, viscin threads can be preserved in the fossil record. A paper published in Grana (1996) looked at the morphology of pollen grains with viscin threads from the Tertiary Period and concluded that “this advanced pollination syndrome using viscin threads as a pollen connecting agent” dates back to at least the Eocene and perhaps much earlier.

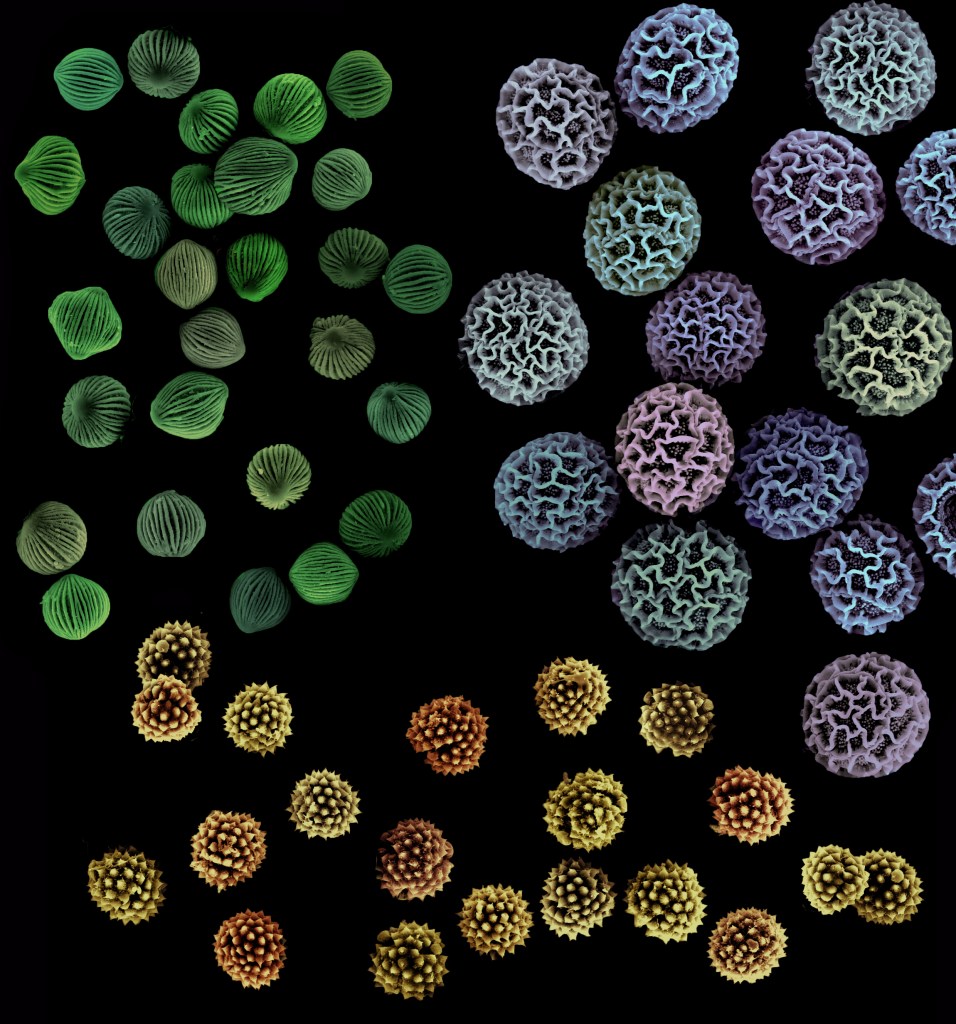

While pollenkitt’s stickiness adheres pollen grains together, viscin threads are more of a tangling device. Single pollen grains or pollen grain groupings called tetrads become tangled up together and then become entangled with a visiting insect, bird, or bat and carried away to a nearby flower. Disentanglement from the pollinator ideally happens when the threads are brushed against the sticky surface of a stigma. The viscin threads themselves vary by species and family. Micheal Hesse, in a paper published in Grana (1981), describes the threads in Onagraceae as “long, numerous, thin, and sculptured” with “knobs, furrows, etc.,” while those in Ericaceae are thin and smooth and those in Caesalpinioideae are thick and smooth.

The length and size of tangled pollen masses also differ by species and can offer clues as to which pollinators visit which flowers. Research published in New Phytologist (2019) looked at the size of pollen thread tangles (PTT) in 13 different species of Rhododendron. They also noted which pollinators visited each species and how often they visited. The researchers found that species presenting pollen in small but abundant PTT were visited by bees, and those with large but few PTT were visited by birds and Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths). Bees also visited the flowers more frequently than birds and Lepidoptera. Bees collect and consume pollen. Between visits to anthers, they spend time grooming themselves, removing pollen clusters from their bodies and packing them into corbiculae (i.e. pollen baskets) for later*. Birds and Lepidoptera don’t groom pollen from their bodies and don’t collect it. In the authors terms, this “suggests pollinator-mediated selection on pollen packaging strategies.” Since flowers pollinated by bees lose much of their pollen in the process, they present it in smaller packages, and since flowers pollinated by birds and Lepidoptera are visited less frequently, their pollen packages are larger.

This is an example of the pollen presentation theory, and is something we will revisit as the Year of Pollination continues.

*This applies specifically to bee species that have corbiculae, and many bee species do not.