If it isn’t clear by now from my Weeds of Boise series and countless other posts, I happen to be interested in the flora and fauna of urban areas. Urban ecology is a fascinating field of study, and I’m not sure that it gets the attention it deserves. Nature is not some far away place, and you shouldn’t have to leave city limits to go in search of it. Remarkably, nature exists right outside your front door, even if you live in the middle of a massive city. It may be a different sort of nature than the one you might find in a national forest or a state park, and it may be composed of species introduced from all corners of the world, but it is still a collection of living organisms interacting with each other and the surrounding environment in unique and important ways. The question is, can you grow to appreciate nearby nature and recognize that the ecological interactions that exist within the context of a city are just as valid as those you’ll find outside of our built environments?

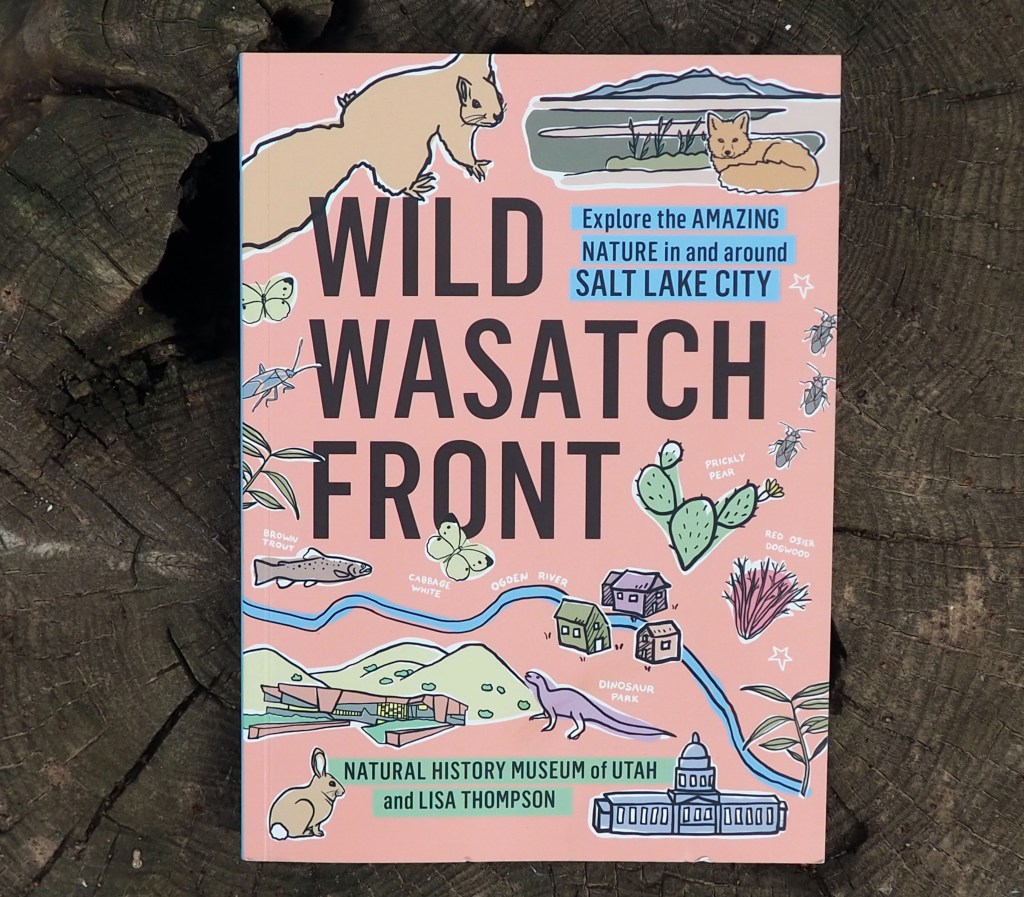

Luckily, there are resources that can help you with that, including a recent book compiled by Lisa Thompson and others at the Natural History Museum of Utah (NHMU). It’s called Wild Wasatch Front, and it’s of particular interest to me because it covers a region that’s relatively close by, and our two locations share a number of similarities. Plus, I played a small role in reviewing some of the plants (specifically the weeds) that ended up in the book (Sierra would insist that I mention this, so there you go). Similar books exist for other regions across North America and elsewhere, so I encourage you to seek out a book that applies to your hometown.

The Wasatch Front is a metropolitan region in north-central Utah that spans the western side of the Wasatch Mountains and includes a long string of cities and towns extending for many miles in all directions. Included in that list of cities is Salt Lake City, the state’s capitol and largest city in the state. The idea for a book about urban nature in the Wasatch Front was inspired by an exhibit at NHMU called “Nature All Around Us.” The exhibit and resulting book offer a new perspective for those insisting that “nature and cities cannot coexist” or that the nature found in cities is influenced by humans and therefore shouldn’t be considered “real.” Hundreds of organisms making a life for themselves within the boundaries of our cities might argue otherwise.

Wild Wasatch Front is divided into three main sections, with each section being worth the price of the book on its own. First there are a series of essays about urban nature and ecology. Names you might recognize, including Emma Marris and Riley Black, contributed to the book, as well as several other people that live and work in the western U.S. and have an interest in nature and environmental issues, especially as they relate to cities. Novel ecosystems is a reoccurring theme, not just in the essays but throughout the book. In her essay, Sarah Jack Hinners writes, “urban nature is a mixture of the intentional and the unintentional,” adding that “for every tree or rosebush or lawn that we plant and carefully nurture, there are multitudes of other plants and animals that grow and thrive uninvited and unnurtured by us.”

The largest section in the book is a field guide, profiling 127 plus species that call the Wasatch Front home, some native and some transplants. This section is divided into subsections that include birds, invertebrates, fungi and lichen, mammals, reptiles and amphibians, street trees, and wild plants. The entry for each species includes a brief description, a few interesting facts, and details on how and where to find them, accompanied by images. With the variety of creatures covered, you are sure to find something that interests you and a reason to go out looking for your favorites. You may even learn something new about a species you’ve been seeing for years, such as house finches. It turns out that the colorful patches on a male house finch are the result of the plants they eat. These patches can be red, orange, or yellow. The redder the better though, because female house finches seek out mates with this coloration.

Naturally, my focus was mainly aimed at the plants covered in this section. I appreciated the mixture of native and introduced plants, even the inclusion of plants considered to be invasive. Instead of vilifying these species, there is an attempt to understand them and find value in them, even in spite of the concerns and negative opinions held about them. Box elder (Acer negundo) is an example of a plant that has both native and introduced populations. Once widely planted in yards and on farms, this tree has “fallen out of favor.” Its weak wood (a result of growing so quickly), can result in a messy, unattractive tree, making it a poor choice for a street tree. However, it propagates itself readily and shows up in vacant lots and other urban locations that receive minimal management and human attention. In the Wasatch Front, you can find box elders that are native, naturalized, and cultivated, an unlikely scenario unique to urban areas.

The third and final section of the book is a guide to 21 different hikes and field trips in and around the Wasatch Front. Each field trip features a hand-drawn map and some basic notes about the hike. Details about what can be seen along the way are included in the descriptions, which are sure to entice you into visiting. Whether or not you think you’ll ever make it out to any of these spots, this section is still worth reading if only for the ongoing discussions about urban ecology. For example, in the entry for Gib’s Loop, abrupt changes in land ownership and land use (a common experience when hiking in urban areas) is addressed: “Human impacts in the foothills…don’t end at backyard fences, and many animals use resources in both habitats. It’s more interesting to think of cities and the surrounding foothills as part of an interconnected system rather than separate and distinct.”

The field trip section is also used as a teaching opportunity to describe more of the species you’ll find in the Wasatch Front. In the entry for Creekside Park, learn how to identify creeping mahonia (Berberis repens), with its low growing habit and matte leaves, and compare it to Oregon grape (B. aquifolium), with its more upright habit and shinier leaves.

Last year, in anticipation of Wild Wasatch Front, I came across another book with a similar focus. This book was put out by a group called The Urban Field Naturalist Project, headquartered in Australia. Their book, A Guide to the Creatures in Your Neighbourhood, encourages its readers to become urban naturalists and offers resources to help them get started. Just like Wild Wasatch Front, the bulk of the book is a field guide to species found in and around urban areas (in Australia, of course). In place of a guide to hikes and field trips, there are instructions on how to start nature journaling, which is a key component of becoming an urban field naturalist. Getting outside and learning to recognize nearby nature is step one, documenting what you see and sharing those observations with others is step two. Taken together, these two books will help you gain a better appreciation for urban nature and will hopefully inspire you to work to conserve what is there and make room for more.